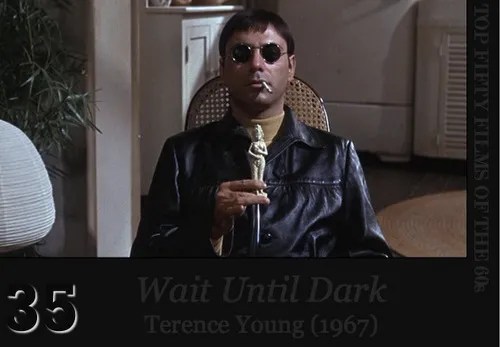

#35 — Wait Until Dark (Terence Young, 1967)

The year before Wait Until Dark was released as a film, it made its stage debut, playing Broadway under the direction of Arthur Penn. Whether by intent or as a result of the quick turnaround from stage to screen, the film feels locked into its origins. With most of the action confined to a single apartment, it’s terrifically easy to imagine the story playing out in a theater. Often, that exact trait can be stifling to a film, making it feel not just stage-derived but stagebound, corralled into a stultifying passivity that ignores the boundless possibilities of film. I suppose some might see Wait Until Dark in similar terms, but I find it’s clear fidelity to the initial work to be exactly the inspiration needed to elevate it. Director Terence Young effectively levels his creativity against the restraints, keeping the film visually interesting while largely moving around a single confined space. Beyond ratcheting up the tension, the relatively close quarters allows the audience to know the setting intimately, making every troublesome shift of the terrain, physical and psychological, all the more harrowing.

It helps immeasurably the Young is working with actors who are fully committed to their roles. Playing Suzy Hendrix, the blind woman terrorized in her own home by thugs trying to retrieve a doll stuffed with valuable drugs, Audrey Hepburn may very well have been contemplating the effective end of her adulation-filled career (it would be nearly ten years before she worked again after this film), but that doesn’t mean she was detached at all. For the character and the film to be effective, Suzy has to be more than simply a victim. If that’s the approach, the finished product is merely exploitation, assaulting a helpless person to spin the stomachs of all who observe. Hepburn understands this, and develops Suzy’s intellect and instincts. This is a woman who’s needed to survive despite her limitations, and Hepburn always signals the ways Suzy is constantly working out strategies to get out of her dilemma. She’s fearful, but she’s also playing sly defense that goes well beyond the expectations of her assailant, who obviously sees her as easy play.

That assailant, the plainly positioned villain of the piece, known as Roat, is played by Alan Arkin in a thrilling, unpredictable twirl of over the top villainy. Arkin, even then a master of understatement, goes the other way, portraying Roat as almost a cunning bad guy straight out of a overly effusive silent film, but carved with menacing new angles by then current sensibilities. He’s icy and ferocious in turn, conveying the sadism that underlies the character’s plot-driven need to get his hands on an elusive item. Arkin was one of the earliest member of Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe, and he draws on some of the breadth developed there, melding the ability to take his voice and his demeanor down every avenue with a terrifying level of focus.

Wait Until Dark would now certainly be characterized as a suspense film or a thriller, but it clearly has the dark heart of a horror film. Part of its appeal to me, admittedly, is that it represents a time when horror films had different characteristics, were truly about the hold they could have over an audience, the way they could compel people to keep watching even when it make their hearts throb with panic. Now they tend to be about little more than piling disgust upon titillation, relying so much on pure shock to such a degree that nothing of meaning is truly at stake. Wait Until Dark feels like so much more. It has a dignity. The evident loss of that quality in horror films across the past four decades and change is scary in its own right.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.