#29 — Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953)

Roman Holiday comfortably coheres to many of the patterns that have dictated Hollywood-crafted romantic comedies for about as long as the moving pictures started to talk. There’s the upstanding man’s man, who may be a little gruff but that’s only because he’s sensible. And then there’s the sprightly, headstrong, mildly bratty younger woman–practically a girl in some respects–who buzzes around him. Naturally, she has a great deal of personal wealth, although she plays that down. He gently but clearly puts her in her place a few times, and she gets him to loosen up. Unlikely as their coupling may be under ordinary circumstances, love is clearly a destination, inevitable and charmed. There are a few things that distinguish Roman Holiday, including the Italian setting alluded to the in the title, representative of the travelogue approach American film increasing took throughout the fifties, distinguishing themselves from the rigid sound stages of the booming medium of television. Nothing is more responsible for its elevation from standard fare, though, that the new starlet in the leading role. Audrey Hepburn wasn’t making her screen debut in the film, but it was her first major part. Few performers announced themselves as fully formed and boundlessly charming in quite the way Hepburn did as Princess Ann.

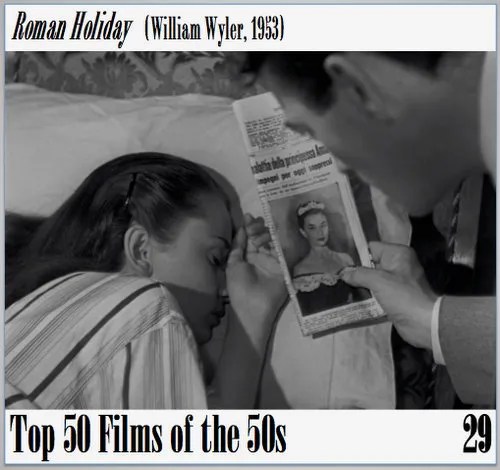

Hepburn, twenty-four years old at the time of the film’s release, won a Best Actress Academy Award for her performance (making her, at the time, the third-youngest to win in the category), and it’s not hard to see why, even without studying her competitors. She has an effortless charm and infectious, ebullient sense of freedom as the youthful disgruntled with her locked-in lot in life. When she flees her overbearing handlers for an unfettered experience of Rome–of the entire world outside her palace walls, really–Hepburn manages to make it less an act of petulant rebellion than a deeply felt expression of the most natural human instinct. Hepburn’s vivid spirit carried through a small legion of signature roles in her career and then arguably even more so in her humanitarian efforts after she decided to largely forgo acting. That began here from the first moments of the film, as she lolled in bed mocking the itinerary laid out for her. There are more famous moments–an impulsive haircut, a scooter ride across the city, a very genuine reaction of shock and delight when a trick is played on her at a landmark carving–but the wonders of the performance are laced consistently throughout.

William Wyler directs with steady assurance and a shrewd instincts that all of the grace and beauty of Rome are ultimately secondary to the need for the characters to be worthwhile. Against Hepburn, Gregory Peck gives his own charismatic performance, his usual oak tree composure regularly disarmed by the joyful gamine before him. His evident flinty pleasure at playing off Hepburn knocks any crustiness of the plot contrivances (his character is a reporter stringing along the princess in her masquerade in hopes of snaring a big story). Eventually, it comes to seem that Peck’s character is prolonging the situation for the simplest, most understandable of reasons: he wants to spend more time with this young woman. As Roman Holiday demonstrated, and the rest of Hepburn’s career confirmed, it’s a blameless instinct.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.