It was in high school that I started defensively insisting on the artistic value of comic book storytelling. Although in deference to the subject of this point, I should say it was co-mix narratives I was stumping for. Spiegelman prefers that nomenclature, undoubtedly in part because it is has some of the hardscrabble spirit of the term “comix,” which was used for the underground, head shop publications that served as his developmental home. But Spiegelman was even more specific in his choice, adding the hyphen to emphasize the two different words parts, each suggesting an intermingling of elements, in this case words and pictures. If comic inevitably implied humor — fine for Richie Rich, less so for, say, a story about the Holocaust — co-mix could be anything, as long as it has the requisite melding of language and visuals.

Spiegelman remains a tireless advocate for the form I once breathlessly raved about. The cartoonist has often been at his most compelling when talking about some of the finest practitioners of his chosen craft, including Charles M. Schulz and Plastic Man creator Jack Cole. I once saw him deliver a guest lecture at the University of Wisconsin in which he spent a remarkable amount of time analyzing a totally bonkers Batman page drawn by Neal Adams. Spiegelman soaks up the history of the form and ponders over it with the pervasive anxiety of a restless intellectual. It is the gratifying cognitive effort of a person who never stops thinking about what he can do as a creator, specifically how he can push the established limits of co-mix to the point at which they splinter, opening up entirely new possibilities. Spiegelman first rose to greater prominence co-editing (with his wife and future New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly) the anthology publication Raw, which certainly brought him into contact with some of the most daring material being crafted at the time. It was also in those pages that Spiegelman started his signature work, maybe the one co-mix creation that can be called a masterpiece with no hesitation whatsoever.

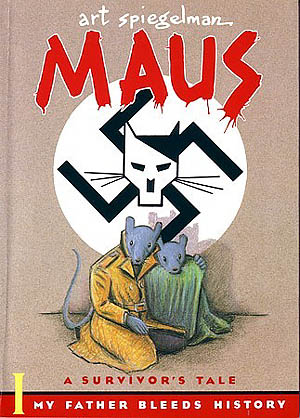

Maus, subtitled A Survivor’s Tale, was based on Spiegelman’s interviews with his father, Vladek, about his experiences as a Jew in Nazi Germany, including internment at a concentration camp. The book is simultaneously about Vladek’s story and the combative relationship between father and son, which the attempt at capturing history soothes and exacerbates in turn. The book has layers upon layers, including eventual metafictional touches as Spiegelman frets about the success of a project built on staggering human tragedy, all of which are somehow given added resonance by the writer-artist’s decision to recast the humans as animals, the Jews depicted as mice, the Nazis as cats and so on. At first blush, it seems like some sort of a sick joke — and it undoubtedly took some a little longer to come around to the potency of Spiegelman’s vision simply because of the strangeness of images that at first glance could look like they belong on the Sunday funnies page — but the artistic choice had the effect of snapping an oft-told story out of the haze of familiarity. There was a plainspokenness to the storytelling that was at odds with the anthropomorphized animals, a dichotomy that enlivened Maus. It was something like Animal Farm without the guardedness of allegory.

Upon its completion, with the 1992 publication of the second volume (subtitled And Here My Troubles Began), the acclaim for Maus reached the stratosphere, including the awarding of a Pulitzer Prize, the first time the honor was bestowed on a graphic novel. In fact, it remains the only such work celebrated by the Pulitzer committee, despite recent worthy contenders such as David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, Chris Ware’s Building Stories, and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? I really thought any of those could have joined with Maus in the official literary achievement record books, although I can completely understand the reluctance of the Pulitzer folks to put another book on that particular shelf. Maus stands alone as a towering achievement, at a level few other books of any sort reach, much less fellow efforts in co-mix. As I noted, I tediously argued for the literary worthiness of graphic storytelling when I was younger. When I held up Maus as an example, it was the one time I was assuredly correct in my claim.

Previously…

—An Introduction

—Margaret Atwood

—Anne Tyler

—Michael Chabon

—Ian McEwan

—Don DeLillo

—Stephen King

—John Steinbeck

—Donna Tartt

—Jonathan Lethem

—Bradley Denton

—Zadie Smith

—Nick Hornby

—Kurt Vonnegut

—Thomas Hardy

—Harlan Ellison

—Dave Eggers

—William Greider

—Alan Moore

—Terrence McNally

—Elmore Leonard

—Jonathan Franzen

—Nicole Krauss

—Mike Royko

—Simon Callow

—Steve Martin

—John Updike

—Roger Angell

—Bill Watterson

—William Shakespeare

—Sarah Vowell

—Douglas Adams

—Doris Kearns Goodwin

—Clive Barker

—Jon Krakauer

—John Darnielle

—Richard Price

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

8 thoughts on “My Writers: Art Spiegelman”