There are times in the process of seeing, writing about, and, yes, ranking films, when the best feature of the year is immediately evident upon first viewing of it. For me, that was the case with Children of Men. That’s not such a feat in some respects — it was a December release, after all — but it was also a movie that was at least somewhat off the radar, having missed the screening deadline for many critics to include it in their year-end tallies, since that ritual had already moved up to a place on the calendar well before the midnight countdown of New Year’s Eve began. The film is set in 2027, less than ten years from now. If anything, it appears Cuarón and his collaborators were overly optimistic about how long it would take us to get to this broken version of society. I wrote and published this review at my former online home, with the experience of seeing the film still recent and raw.

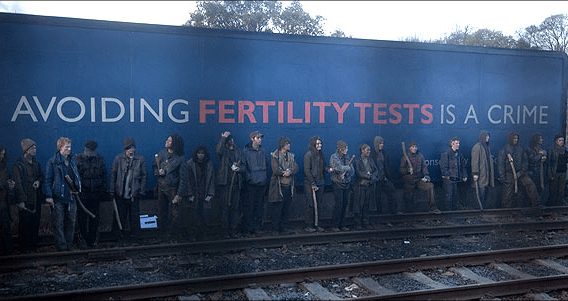

Alfonso Cuarón’s new film Children of Men is set twenty years in the future and begins as society mourns the death of the world’s youngest person, an 18-year-old male. A generation of unexplained infertility has thrown the world into chaos. England seemingly stands as one of the few intact countries, and it has become a brutal, totalitarian police state, rounding up immigrants (referred to as “fugees”) for confinement and deportation. This information is not delivered with clunky exposition or other tired film contrivances. We know this because we are absolutely immersed in the world of the film. Cuarón skillfully lets the details be revealed by the day-to-day challenges the characters face and the central quest which ignites the plot.

That artful assembly of the building blocks of the story is only the beginning of Cuarón’s accomplishment. Children of Men is a parade of astonishing scenes, notable for their simple wisdom, thrilling confidence, and, in a few key instances, bravura technique. Cuarón inserts some extended tracking shots that are absolutely mind-boggling, holding scenes for long stretches as action unfolds at a heart-racing rate. Whether doing this in the cramped confines of a small vehicle or across blocks of a city transformed into a war zone, he enhances the splendidly offbeat shot choice with perfectly choreographed action in the frame. The image is thick with movement and detail.

This isn’t indulgent technical showboating, like sending a camera through a coffee pot handle just because it’s achievable. Cuarón’s cinematic wizardry has a real purpose: plunging the audience as deeply into the action as possible. Jean-Luc Godard famously said “every edit is a lie,” and Cuarón proves the truth of that statement with these elegant, energized continuous shots. The tension of the scenes is accentuated because we feel completely in the moment, watching action unfold as if we were embedded into the scenes. We are there for the horrors and the momentary surges of hope. Some directors take approaches like this because it is cool, superficially enlivening due to mere difference; Cuarón does it because it’s the absolutely, unequivocally the best way to stage the roiling trauma of the film’s most fraught, compelling segments.

It is also a film fiercely alive with ideas. As in the best science fiction, Children of Men is set in the future to better evaluate the here and now. The socio-political commentary throughout is understated enough to avoid becoming didactic but rich enough to give the film a rewarding relevance. Corollaries can be drawn to multiple ideological battles raging across the Yahoo! news page with the film standing as equal parts cautionary tale and bleak predictor of the inevitable.

While the gifted cast yields no shortage of performers and performances worth celebrating — Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Claire-Hope Ashitey, and the uncommonly rascally Michael Caine among them — lead Clive Owen is given a complex, internalized character and the necessity of holding the film together, and he responds with deceptively quiet and soundly sensational work. He carries the pain and strain of his character with precious few opportunities for overt emoting. It’s simply not the sort of film that will gift an actor with scenes of showy grandstanding that can readily garner awards attention, but it demands a control and focus that is, finally, far more impressive.

It is another thing to for a film to have something to say, to have a message or a worldview to convey. It is another, more elusive achievement to construct that film so it carries its ideas with the added weight of great artistry. That’s precisely what Cuarón has done with Children of Men.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.