On this Academy Awards weekend, I’ll reach back to the review I wrote about the film that earned Helen Mirren her Best Actress in a Leading Role trophy. This was first posted at my original online home.

Stephen Frears’ new film The Queen begins with a slightly awkward scene in which Queen Elizabeth II discusses the burgeoning popularity of Prime Minister candidate Tony Blair with a man painting her portrait. It if a brief scene which doesn’t so much introduce the Queen as establish the official relationship between the monarchy and the elected government. The film then shifts to a separate shot on which the camera pans up the Queen, dressed in all her royal finery, settling on a close-up of her face as she look directly at the viewer. The film’s title appears next to her head, and momentarily, it feels like the strangely straightforward opening to some new BBC sitcom about the Royal Family.

This tiniest of stumbles is the only thing at all problematic about The Queen. Frears has made a marvelous film.

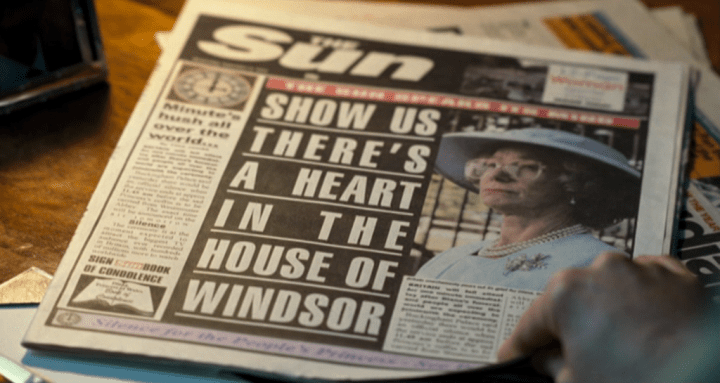

In focusing on a single, meaningful week, the film captures all the dilemmas of a modern monarchy. Tony Blair has just been elected Prime Minister when word comes from France that Princess Diana has been killed in a car crash. Blair instinctively, astutely determines that this will be cause for national mourning and responds accordingly. The Royals do not, choosing to remain silent and detached, their decision fueled dually by an animosity towards the woman whose aversion to their ways helped end her marriage into the family and an adherence to the legendary British emotional reserve they feel it is their place to exemplify.

This situation, rich, famed and painfully recent, provides the perfect window into the conflicts of a ruling class whose power is now strictly ceremonial. They are so utterly removed from their subjects, indeed from the ways of the entire world, that they have no sense whatsoever of how to proceed. Helen Mirren plays the Queen with an expected regal composure and confidence. She also excels at finding the hidden moments of vulnerability in the women, the fleeting times when she will allow some vulnerability to show, while openly considering her fading popularity or gazing at the beauty of nature. Her performance is equalled by that of Michael Sheen as Prime Minister Blair. It is he who privately rails against the Royal, but also reaches out to them, trying to gently coax them towards the right political decisions out of devotion to the country he has been chosen to govern.

The smart script by Peter Morgan (who’s also a credited writer on the far less successful The Last King of Scotland) never stoops to pushing this situations into melodramatic excess. The drama emerges from the reality of the situations, not from manufactured, overwrought battles. The conflicts are finally so simple and yet so effective: the Royals chatting aimlessly about daily plans as they watch other world leaders extoll the virtues of Diana on the evening news, utterly oblivious to their need to do the same. There is even rich contrast in the plainly captured images of the Queen and Tony Blair talking on the telephone, each in their own home library, the Queen’s a large, tasteful collection of old tomes, and Blair’s a batch of novels and paperbacks shoved into shelves with toys and knickknacks. It’s just set dressing, but Frears has the confidence to let these background details tell the story.

Not that the film is a strict polemic against the Royal Family. It often has sympathy for them. They may have been oblivious to the changing world around them, but it allows for the suggestion that their devotion to tradition might have some nobility to it. And, in the wake of the global grief over Diana’s death, the film does allow Prince Phillip to make one the most pertinent, pointed observations: “Sleeping in the streets and pulling out their hair for someone they never knew. And they think we’re mad!”

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.