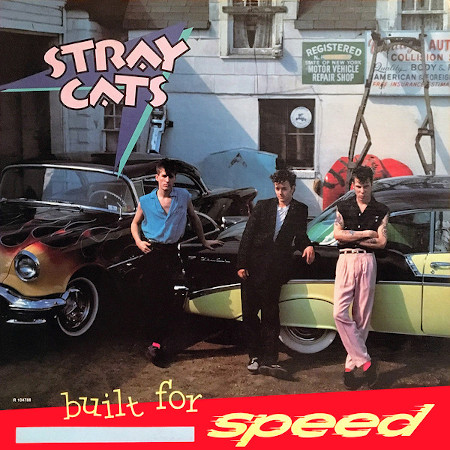

40. Stray Cats, Built for Speed (1982)

“Crowds around the world are receptive,” declared Brian Setzer, frontman of Stray Cats, shortly after the release of Built for Speed. “The kids were ready for us, but the record companies weren’t. Now everybody’s ready, and we’re going to rock ’em all.”

The initial record company aversion was significant enough to inspire Stray Cats to roam from their homeland alleyways to the U.K. in search of better prospects. In the latter portion of the nineteen-seventies, Setzer dropped out of schools and concentrated on picking up every gig he could as a guitar player. Eventually, his orbit aligned with those of drummer Slim Jim Phantom and bassist Lee Rocker. Setzer recruited them to be help fill out the sound when he booked shows as a retro act specializing in the sort of headlong rockabilly practically unheard in clubs since the heyday of Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. Eliding bookers’ collective resistance to schedule the same band on multiple nights, the trio constantly changed their name, but they always included “Cats” in there somewhere as a sly signal to their burgeoning fan base. Even as they leveled up to major New York City venues, such as CBGB and Max’s Kansas City, the band didn’t generate the barest of interest from record labels. After getting word that there was a booming scene for rockabilly acts in London, the three of them decided to relocate. They had to buy an extra plane ticket for Rocker’s double bass.

The American Invasion strategy proved sound. By then settled on Stray Cats as a permanent name, the band was a quick sensation, playing shows to wildly rapturous crowds and ardently pursued by a bevy of U.K. labels. They had a few fortuitous turns, too, such as Dave Edmunds attending a concert and deciding he’d found roots-rocking kindred spirits and offered to producer Stray Cats’ debut album. They further benefited from their origins on the other side of the Atlantic. The London crowds knew rockabilly was American music, so the Americans playing it must be more authentic. Stray Cats shrewdly tailored their originals to this audience, writing lyrics about local environs and pub life. For example, “Rumble in Brighton” is a bustling blazer about modern greasers and skinheads duking it out: “There’s the rockabilly cats/ With their pomps real high/ Wearin’ black drape coats/ All real gone guys/ Cool skinheads with their rolled up jeans/ Lookin’ real rough and mighty mean.”

“Rumble in Brighton” appears on Stray Cats’ self-titled debut, released in 1981. The follow-up, Gonna Ball, came out in the same calendar year. Although those albums enjoyed commercial success in the U.K., neither was released stateside. Instead, Stray Cats signed a deal with EMI America, and the labeled culled a set of tracks from the first two studio full-lengths. They added one song that hadn’t been released yet and borrowed its title for the compilation. Ironically, “Built for Speed” is was of the more swingy, easygoing tunes in the band’s repertoire at the moment, but the sentiment of the title suited what was generally found in the album’s grooves.

Built for Speed hit record stores in the summer of 1982. Although it took a little time to really get moving, the album was a formidable performer. It spent fifteen straight weeks in the runner-up position on the Billboard album chart, first unable to get the lengthy stay at the top of Men at Work’s Business as Usual and then leapfrogged by Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Two of its singles — the frisky “Rock This Town” and icy cool “Stray Cat Strut” — made the Top 10 in the U.S.

“I think most of those cats are tired of seeing the same old bands for so long,” Setzer told a reporter in an attempt to explain the band’s smashing success before going on to specifically target the prog rock warhorses who were falling out of favor. “They need a group they can relate to, not just a bunch of old guys with beards or bald heads and thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment. They want somebody young, fun — a group like us that plays simple rock ‘n’ roll.”

At twenty-three years of age, Setzer was indeed a comparative whippersnapper when he made those remarks, but it’s still an amusing sentiment coming from a guy whose art was far more old-fashioned that music of those he was criticizing. Built for Speed paid proper tribute to the acts that set the Stray Cats template with a trio of covers: “Double Talkin’ Baby,” “Jeanie, Jeanie, Jeanie,” “Baby Blue Eyes,” originally recorded by Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and Johnny Burnette and the Rock ‘n Roll Trio, respectively. Each of those songs was at least a quarter-century old. At times, as with the moony ballad “Lonely Summer Nights,” the new numbers sounded like they could from a yet more distant pop past. Stray Cats play it all with verve and conviction, but they were recycling more than inventing.

Like many other throwbacks that find a place of cultural favor, the shine lasted only so long. The band’s next studio album (which was the first recorded with the knowledge that it would get a U.S. release), Rant n’ Rave with the Stray Cats, underperformed, though it did account for one more Billboard Top 40 single: “(She’s) Sexy + 17.” Simultaneously, the three musicians were growing apart, undone by their success and the newfound influx of competing opportunities. Following the tour in support of Rant n’ Rave with the Stray Cats, Setzer announced the band was over. Multiple reunions followed, the first one occurring so quickly that only three years passed between the album that supposed served as curtain call and the one touted as their comeback. The damage was done. Stray Cats were never again a significant presence on the album or singles charts.

”It was silly to break up the Stray Cats at the peak of our success,” Setzer reflected many years later. ”We probably had people yelling in our years, ‘Oh, you don’t need them. You can do better on your own.’ We were just stupid kids, really. We should have acted like men, licked our wounds, and come out swinging.”

39. Duran Duran, Rio (1982)

Rio, the second studio album by Duran Duran, debuted on the Billboard album chart at #164 on June 5, 1982. It made a slow climb from there before spending two weeks at #122 in mid-July. Then it started to fall again. By early August, it was sitting at #165 and seemed to be a stiff in the U.S. market.

Even as U.S. record buyers were striding right past Rio to pluck Paul McCartney’s Tug of War or Asia’s self-titled debut off the new releases shelf, the programmers at MTV were intrigued by a new submission titled “Hungry Like the Wolf.” Directed by Russell Mulcahy as part of a planned visual album that could be released to the booming home video market, the clip was more striking that most of the similar promotional efforts at the time. There was a cinematic sweep to Mulcahy’s visual storytelling, which further benefited from a having a band full of photogenic gents gamely playing along. Filmed in Sri Lanka, the video casts lead singer Simon Le Bon was as a suave, Indiana Jones type and his bandmates — keyboardist Nick Rhodes, bassist John Taylor, drummer Roger Taylor, and guitarist Andy Taylor – as stylish cohorts who trail after him.

“This video comes on, and I’m entranced,” recalled Lori Majewski, co-author of the definitive Mad World: An Oral History of New Wave Artists and Songs that Defined the 1980s. “And by the time it gets to the part where John Taylor is showing the Polaroid of the missing Simon Le Bon, and he shakes his head no, I was entranced. And from then on, everything I’ve done in my life has been about Duran Duran.”

Majewski’s experience was shared broadly by other young fans — particularly teenaged girls — who tuned into the music video cable network, which had then been in operation for only about a year. Compared against most of the other videos at the time, usually made on the cheap with little more going on that acts miming along to their songs and maybe clowning around, “Hungry Like the Wolf” was explosively ambitious. It didn’t hurt that the song is arresting all on its own, vibrant in its yearning energy.

“I am very grateful that our timing — our accidental timing — with the advent of music video was so fortuitous,” Rhodes observed several years down the road from the experience of blowing up on MTV. “If we’d been five years later, I think the exciting bit was already over; if we’d been five years earlier, we would have been usurped by newer, younger bands. It just happened that we were at the right place at the right time.”

As MTV was championing Duran Duran, the band’s North American label, Capitol Records, made an offer. If Duran Duran would remix some of the songs to better align them with the perceived preferences of U.S. radio, the band’s music would get a recommitted promotional push. David Kershenbaum, then best known as Joe Jackson’s go-to producer, was brought it to slick up the material. He worked with the band to remix three cuts from Rio and the earlier single “Girls on Film,” giving them all muscular, dance-driven enhancements. The new versions were released in September on an EP titled Carnival, which did brisk enough business to convince all involved that Kershenbaum’s approach worked; the week Carnival peaked at #98 on the Billboard chart, Rio was scuffling some forty places behind it. Kershenbaum remixed the entirety of the first side of Rio, and Capitol quietly released it, telling music journalists that the updates stemmed from the band’s collective dissatisfaction with the previous versions of the songs. Around a month later, Rio moved into the Top 100 for the first time, and it was in the Top 10 by the end of February. A week before that, “Hungry Like the Wolf” crossed into Top 10 of the singles chart; it remained in the Top 10 for nine weeks, peaking at #3.

MTV remained on board the whole time, so much so that Duran Duran was practically the house band for those boom years of the network. Much as success was what Duran Duran was chasing, they had some misgivings about how they arrived there. They still fancied themselves as denizens of rock’s underground, more Joy Division than Journey. There are unmistakably pop inclinations emerging on Rio, even before the tinkering, but Duran Duran assessed their tilts toward the mainstream as akin to those by notably iconoclastic acts such as David Bowie and Roxy Music. That they were suddenly going straight for the throbbing hearts of club-goers took some getting used to.

“The passage of time does allow you to look back with some good grace, and be a little more pragmatic about what things did and what things meant,” Rhodes told Annie Zaleski in an interview she conducted for her 33 & 1/3 book about Rio. “And I think that all of us would say that the Rio album was what set us on our trajectory for not only the next decade but really the rest of our career.”

Admitting that knowledge of the roiling backstory of the album influences this impression, Rio sounds like the work of a band making a transition without all that much intent to do so. The songs that everyone knows are staples of eighties-celebrating radio stations for good reason. The cheeky, vivid title cut (“Moving on the floor now, babe/ You’re a bird of paradise/ Cherry ice cream smile/ I suppose it’s very nice”) and the effusively elegant “Save a Prayer” deserve to stay in recurrent rotation forever. Similarly, “Hold Back the Rain” sounds effortlessly massive in a way that eluded contemporaries that couldn’t help but show the strain when they went big. The material is less compelling when it skews stranger, whether in the ambitious gloom of “Last Chance on the Stairway” (“Funny it’s just like a scene out of Voltaire/ Twisting out of sight/ ‘Cause when all the curtains are pulled back/ We’ll turn and see the circles we’ve traced”) or the improvisatory studio experiment “The Chauffeur” (“And watching lovers part, I feel you smiling/ What glass splinters lie so deep in your mind?/ To tear out from your eyes with a thought to stiffen brooding lies/ And I’ll only watch you leave me further behind”).

If they arrived at their success by a circuitous path quite different than the one they mapped out, Duran Duran intended to take advantage of the clout they amassed. There might have been luck in their rise, but there were a lot of difficult decisions and cleverly orchestrated reinvention, too. As Rio enjoyed its late-breaking dominance of the U.S. charts, the members of Duran Duran insisted that they were using their new opportunity to enhance their creativity rather than simply try to duplicate the triumphs of their recent past. They insisted that their next album, dubbed Seven and the Ragged Tiger, was represented an amazing new peak.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.