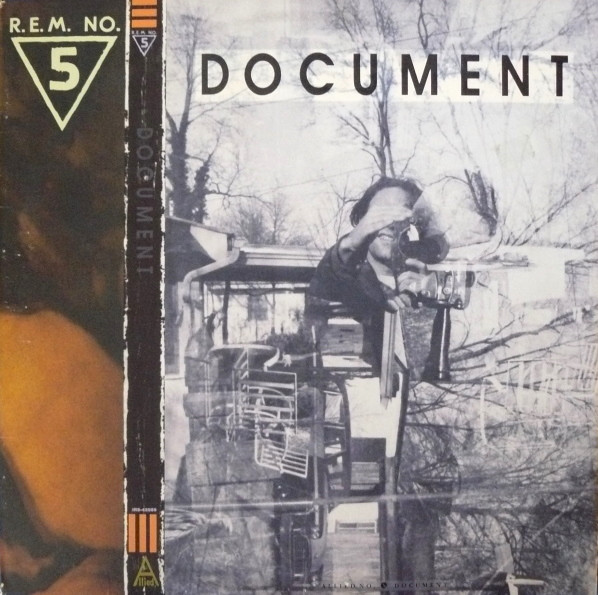

8. R.E.M., Document (1987)

R.E.M. had a message to convey and, more than was previously the case, they wanted to ensure they were understood. Across their first four studio albums, the immediate icons of college rock established and cultivated a persona that emphasized obscurity. The mumbly lead vocals of Michael Stipe, the flat refusal to print lyrics on the inner sleeve, and the routine rejection of interview questions prying into the meaning of individual songs were stones in the bulwark against easy interpretation of their art. The music was accessible and inviting, often built on jangly, folky melodies and, increasingly with each album, musicianship that drew on the fine fundamentals of the lean rock ‘n’ roll that was played by nineteen-sixties garage rock bands. A large part of the early appeal of R.E.M. was the way the stylistic directness of the music contrasted with the willful obliqueness of the lyrics, both in form and presentation.

“In the early days — and I’m talking about up to Document, the first seven years of the band — I saw mystery as a crucial element of seduction,” Stipe told The New Yorker. “Of creating a desirous image — I don’t even know if that’s a word. Mystery was an important part of it. ‘Willful obscurity’ is the term that was used against me, or the band. But there was a useful obscurity that disappeared around Document. And I think, actually, politics is what pulled us away from that. Also, I honed my chops as a lyricist. I wasn’t just reading words that sounded good and that felt emotional and important, which is what Murmur is. Don’t try to make sense of it — it’s as obscure as anything by Sigur Rós or Cocteau Twins. But I did have, or I discovered, a knack for words, and then I worked and worked to make it as good as it could be.”

The shift really started with Lifes Rich Pageant, the band’s fourth album. In addition to Stipe’s singing growing clearer — which it did with each successive release across the first decade or so of the band, until no further enhancement was available or particularly needed — there were songs where the thesis was basically laid out plain. Coincidentally or not, Lifes Rich Pageant was the first R.E.M. album to accumulate enough sales to earn a gold record designation. The rising political fire within R.E.M. that led to a more assertive clarity on that album only lapped higher with another year of Ronald Reagan’s destructive presidency and the corresponding emboldening of right-wing ghouls to roll back decades of social progress in the United States. If they cleared their throats with Lifes Rich Pageant, R.E.M. were ready to start shouting from the tower tops on its follow-up.

“This wave of conservatism, which is leading to what we see as an assault to personal rights and freedoms,” bassist Mike Mills answered when asked about what motivated R.E.M.’s newfound readiness to lift the veil from their artistic intent. “It’s something that we see and feel like we should say something about.”

In other ways, R.E.M. stuck to their recently established model. After working with the same producers on their first two LPs, Murmur and Reckoning, the band tried to avoid repetitiveness is their sound by adopting a policy of switching up the person filling that role every time they went into the studio. When they were enlisted to record a new track for the 1987 romantic comedy Made in Heaven, R.E.M. brought in producer Scott Litt, mostly because they admired his work on the early dB’s record Repercussion. The movie bombed, and the soundtrack followed suit, but R.E.M. liked the results they got from Litt. They moved forward with him as producer for their next album, their fifth overall. The album is Document.

Working with Litt, R.E.M. took the recording of the album more seriously than they had before. According to their own assessment, their studio time had been approached fairly casually on earlier records, with band members sort of drifting in and out, occasionally getting distracted by other pursuits. Maybe R.E.M. were inspired to greater discipline because the message was more pointed or there was a sense that they were properly poised to climb another rung upwards in terms of their popular success. Although the group had occasionally been hounded for hits by I.R.S. Records, their label at the time, the music executives had basically given up on applying that heavy hand. The progress to that point was admirable enough, and R.E.M. could basically be trusted.

“There wasn’t really a lot of pressure on us to follow up a hit record or anything,” drummer Bill Berry said shortly after Document was released. “We’re just a band that’s not going to have hits. We try to make strong records.”

Berry’s prognostication abilities were faulty. With Document, R.E.M. became a band that was going to have some hits. “The One I Love” was released as the album’s first single and, boosted significantly by adoring attention from MTV, broke through in a big way. It wasn’t just R.E.M.’s first Top 40 single; it climbed all the way into the Top 10 of the Billboard chart, presumably in part because some listeners were oblivious to the viciousness at the core of the driving rock song (“This one goes out to the one I’ve left behind/ A simple prop to occupy my time”). Like the Police’s “Every Breath You Take” before it, the hit likely benefited from facile readings of its sentiment by casual radio listeners. It was catchy and sounded like a love song, and that was good enough.

Start to finish, Document is sturdy as a well-designed steel structure. The album opens with “Finest Worksong,” which is all guitar washes, pummeling drums, and howled lyrics that rise to engage the warped priorities of capitalism (“What we want and what we need/ Has been confused, been confused”). From there, the band gets yet more clear in their treatise about the state of the world: “Welcome to the Occupation” hammers away at U.S. meddling in Central America (“Where we propagate confusion/ Primitive and wild/ Fire on the hemisphere below”), and “Exhuming McCarthy” invokes the disgraced senator from Wisconsin and his despicable manipulations of patriotic fervor to persecute anyone who dared to suggest that the nation could do better than constant equivocation to monied marauders (“Vested interest united ties, landed gentry rationalize/ Look who bought the myth, by jingo, buy America”). The first side proceeds to “Disturbance at the Heron House,” which swirls like a brackish whirlpool, and “Strange,” a cover of a standout track from Wire’s seminal Pink Flag LP that R.E.M. gives a roadhouse boogie touch. The side closes out with the propulsive, stream-of-consciousness riot “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine).”

“Side one is probably the best album side we ever did,” guitarist Peter Buck told Mojo several years later. “Right through, it’s like a mini-concept record, although God know I wouldn’t have said that at the time! They’re all songs concentrating on the America of the time, our perception of it. Even the Wire cover fits well. Then side two is the weird stuff and the hit single.”

The hit single leads off that second side, and then comes what Buck terms the weird stuff. “Fireplace” locks in on oddball lyrics that repeat like a mantra until they bizarrely start to make sense (“Hang up your chairs to better sweep/ Clear the floor to dance/ Sweep the floor into the fireplace”) and keeps the music similarly off-kilter with bursting horn parts provided by Steve Berlin, the saxophonist with Los Lobos. “Lightnin’ Hopkins” finds Stipe almost adopting a Gordon Gano drill-bit trill, and “King of Birds” builds a majestic sweep with its tingle of psychedelia against the militaristic drums of Berry. Document closes with “Oddfellows Local 151” which has a bluesy grind and yet sounds like a punk song stretched and slowed, as if played at the darkest depths of the ocean. In a catalog already stuffed with greatness, Document instantly asserted itself as a contender for R.E.M.’s best album.

“After five albums, whether you like us or not, you can’t say that these guys are horrible,” Buck observed. “We’re good. One good record could be a flash in the pan, but five good records aren’t.”

Powered by “The One I Love” and loads of critical acclaim, Document became the first R.E.M. album to make it into the Top 10 of the Billboard album chart, a threshold all but two of its studio album successors would also cross. Around four months after its release, the album was certified platinum, another first for the band. R.E.M were clearly happy with the results; they abandoned the practice of regularly switching up producers and brought back Litt for each of their next five studio albums. Their label bosses gladly took a victory lap.

“I think this is the textbook example of true artists development,” said Jay Boberg, then the president of I.R.S. Records. “The band grows, and the audience grows under terms that the band, the audience, and the record company are all happy with.”

If folks in the I.R.S. Records office were happy, they were probably also nervous. Document was the last album R.E.M. owed the label, and they’d made no secret of their curiosity about what pending free agency might bring.

“I don’t know if it’s a turning point,” Mills said as Document was still on the upswing. “It’s kind of a culmination of things so far — our first radio hit, our first album with any chance to go platinum, the last year of our contract with I.R.S. We’re got to figure out what we’ll do then. Next year should be interesting.”

Mills was a better seer than Berry; the next year was indeed interesting. Just a couple months after Document hit the one million mark in sales, R.E.M. signed with Warner Bros. for a hefty sum and the promise of total creative freedom. Their major label debut, Green, arrived before the end of the year, timed to Election Day.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.