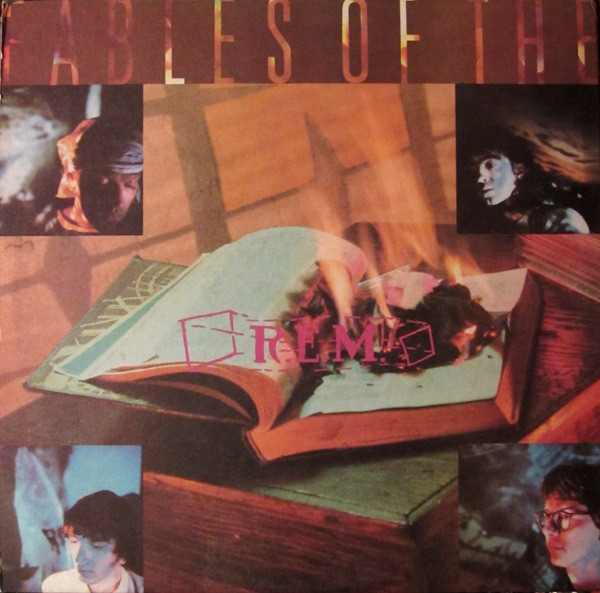

6. R.E.M., Fables of the Reconstruction (1985)

“Lots of kids aren’t willing to listen just to Hall and Oates or whatever,” noted Bill Berry, the drummer of R.E.M., shortly after the release of the band’s third album, Fables of the Reconstruction. “They will turn to the college radio stations, where they can hear new bands, and it has become cool to read fanzines and search out your own bands. There’s this great sense of adventure today. It’s more fun to go in a record store and take a chance on a record you may have read about than just settle for the new Foreigner record or whatever. That’s great because it creates and audience for new bands. I think we were just in the right place at the right time.”

Berry is probably correct that R.E.M. were in the right place at the right time. To a certain degree, though, they were centrally responsibility for shaping that time in that place. Just as college radio was forming a collective identity more distinct than album rock radio that maybe went a little deeper in records, R.E.M. sprung onto the national scene with a debut LP that was smart, insinuating, tonally downbeat, and like nothing that was likely to be played by any station worried about listeners fleeing before the next block of commercials. Murmur was rebellious but in a shuffling, eyes cast downward sort of way, not unlike a lot of the scruffy kids who sought refuge from their alpha, social-striving classmates in a left-of-the-dial broadcast booth. R.E.M.’s emergence was centrally important to college radio defining itself. By the time Fables of the Reconstruction was released, college radio was in more or less its final form and few things sounded as perfectly right than freshly pressed R.E.M. jangle cascading out their transmitter towers coast to coast.

For that third album, though, R.E.M. was determined to not deliver the same old jangle. Their first two albums, Murmur and Reckoning, were critically acclaimed, and they absolutely dominated college radio playlists. It would have been easy for the band to again reunite with Mitch Easter and Don Dixon, producers of those first two outings, and ply their trade in the manner to which the fans had grown happily accustomed. As was often the case throughout their career, the band was adamantly against the safety of repetition. R.E.M. wanted something different, so they cast around for a new person to be their guide in the studio. Relatively quickly, they settled on Joe Boyd, mostly because guitarist Peter Buck admired his work on albums by the Incredible String Band and Nick Drake. Boyd was based in England, so the Georgia band strayed away from the Southern U.S. for the first time in their recording career, setting up in London’s Livingston Studios. As always, R.E.M. were delighted to go their own way rather than adhere to the development of distinct, consistent oeuvre that might please music journalists.

“It’s nice for people to write about us, and that’s a critic’s job — to intellectualize things,” the band’s lead singer, Michael Stipe, told a reporter. “But from the beginning, we never really listened to what anyone said about us. If we had a manifesto in the band, that would be it: ‘We’re going to please ourselves before anyone else.’ We just play what we play.”

Much as R.E.M. sought change, the experience was clearly discombobulating to them. They were a long way from home, and Boyd worked very differently than his predecessors on the producer’s perch. Where Easter and Dixon kept proceedings fairly loose, hoping to capture some of the spontaneity they admired in R.E.M.’s live performances, Boyd favored long sessions of meticulous recording and mixing. The band worried that they were getting lost in all this polishing. Combined with the whirl of rising fame and the pressure of following up two highly acclaimed studio albums, R.E.M. set their creativity to some strange frequencies.

“Theoretically, it’s what I like about rock ‘n’ roll: It’s kinda weird, you can tell the band’s out of their minds, it’s strangely mixed — which is all down to us, not Joe Boyd,” Peter Buck told Mojo several years later when asked to assess Fables of the Reconstruction. “It’s a snapshot of our twenty-four-year-old nervous breakdowns. Joe’s a great guy. I don’t think we handed him the easiest record he’d ever worked on. I think it’s cool. But I also think, ‘Fuck, what were we thinking?'”

When asked for his own reflections on the album, Boyd largely agreed. Although he might have been a little more willing to own up to his part of predicament, he allowed that R.E.M. were at least somewhat perplexing to him.

“I always had a problem with those mixes,” Boyd said. “The group was unhappy, I was unhappy. No one liked the room we were mixing in. Michael was always saying, ‘Turn me down, turn me down,’ and Peter was saying, ‘Turn me down.’ How could you mix a record if everyone wanted to be turned down?”

To be fair, the reduction in volume suited the gentle jamboree vibe that crept into R.E.M.’s songs on Fables of the Reconstruction. Going into the songwriting process, Stipe had been listening to a lot of Appalachian folk music. Because homesickness was also at play, the new material R.E.M. developed felt like it was trying to document their home territory. The chiming “Driver 8” has a deep sense of place (“I saw a treehouse on the outskirts of the farm/ The power lines have floaters so the airplanes won’t get snagged/ The bells are ringing through the town again/ The children look up, all they hear is sky-blue bells ringing”), and the folksy ramble of “Green Grow the Rushes” comes across as a roving troubadour’s recounting of his journeys (“Stay off that highway/ Word is, it’s not so safe/ The grasses that hide the greenback/ The amber waves of grain again/ The amber waves of grain”). The probing, vaguely spooky “Old Man Kensey” includes lyrics added by Jeremy Ayers — a rare instance of someone outside of R.E.M.’s quartet getting a songwriting credit on one of their originals — and tells of an amenable scoundrel, based on a real person, who has a kinship to any number of colorful characters in the canon of Southern Gothic literature.

“It’s weird, because all of our records end up having a central theme, although we never plan it,” Buck said. “And to me, not to put too fine a point on it, this one is home. In listening to it in retrospect, this seems to have a feeling of a particular time and place, not so you could put a date on it. You can’t say, ‘Oh, this is Athens, Georgia, 1985’ or ‘Georgia 1885.’ But when the record’s finished, you seem to, at least I seem to, get a feeling of a sense of community or a sense that this was written about a certain place.”

The solidity of time and place is sent skidding by the ways R.E.M. expands their sonic palette on the album. As if making a feint in the direction of expectations, album opener “Life and How to Live It” has a delicate intro that could have shimmering into being on Murmur before the cut swerves into plucky, vivacious rock. The band conjure up a radiant tingle on “Maps and Legends,” partially because of the splendid harmony vocals of bassist Mike Mills, and make a thick, mesmerizing sound on “Kohoutek.” “Can’t Get There from Here” is a bounding, energizing track that Buck described as a funk parody, “Auctioneer (Another Engine)” has an intriguing halting cadence, and “Feeling Gravitys Pull” is luxuriantly enveloping.

Although Fables of the Reconstruction was dominant on the college charts, the requisite grousing about the band simply not being as good as they once were began in earnest here. For a long time, this was the album that was most commonly cited as R.E.M.’s low point, at least until Berry left the band, and the discography grew much spottier across the latter portion of their career. And this set of songs does represent the first point that R.E.M. seemed fallible; the album peters out with “Good Advices” and “Wendell Gee,” both of which are tepid. The band didn’t like being on that pedestal anyway.

“A lot of the hype behind us is bullshit, part of the same old tradition we were inspired to work against,” Stipe said at the time. “We make a lot of mistakes, but I think we’re good anyway. I’m proud of what we’ve achieved.”

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.