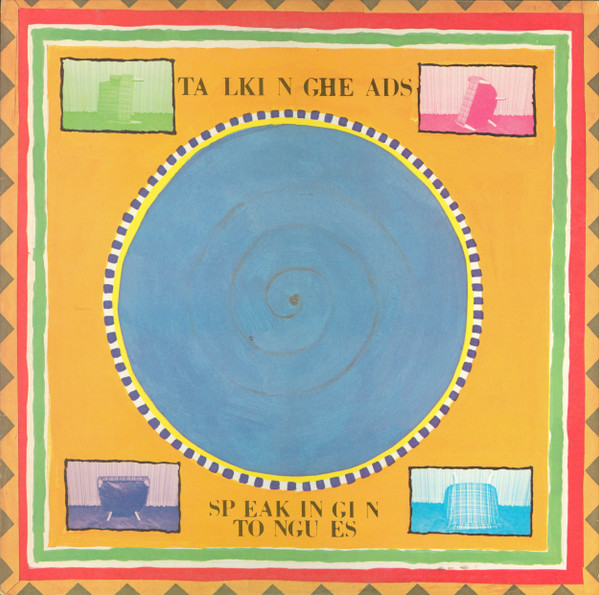

5. Talking Heads, Speaking in Tongues (1983)

Nearly three full years passed between the release of Talking Heads’ fourth album, Remain in Light, and its proper studio follow-up, Speaking in Tongues. The span of time was long enough during that particular era of pop music to inspire speculation in the music press that the band had reached its endpoint. The theory was often presented with the corroborating evidence of the individual members’ highly visible outside projects. Between the two studio albums, bassist Tina Weymouth and drummer Chris Frantz released a debut LP their newly formed group Tom Tom Club (and they had another soon on the way), keyboardist and guitarist Jerry Harrison put out a solo album, and the endlessly restless frontman David Byrne took a slew of projects, among them composing music for a Twyla Tharp dance piece and working on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, an album with regular Talking Heads collaborator Brian Eno. It was that last endeavor that arguably prevented Talking Heads from permanently going their separate ways at that moment.

Strain had arisen in the band on their last couple albums, mostly stemming from the increasingly insular relationship between Eno, who served as producer on their second through fourth albums, and Byrne. To different degrees, the other three Talking Heads felt boxed out from creative decision-making and, maybe worse, appropriate credit for their contributions. When the band started discussing a fifth album, it was clear Eno wouldn’t be involved, supposedly because he and Byrne had a bit of a falling out during the making of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Eno’s absence provided some hope that the band could rectify their internal rocky relationships.

“We never said, ‘The band’s breaking up’ to each other,” Weymouth noted bluntly at the time. “The problem went away because Eno went away.”

With Eno gone, Talking Heads went on the hunt for a new producer. They quickly landed on Tony Visconti as a candidate, appreciative of his extensive work with David Bowie. As interesting as a Visconti-produced Talking Heads album would surely be, he turned them down with the assurance that they were well past the point of needing someone like him behind the studio glass.

“I remember going to Tony Visconti, and meeting with him at the Hilton Hotel where he was packing his bags to go to London,” Frantz later explained. “I said, ‘Tony, how’d you like to produce the new Talking Heads album? We’re going to make one pretty soon.’ And he said, ‘You don’t need a producer. You just need a good engineer. Produce it yourself.’ So that’s what we did.”

The good engineer Talking Heads got was Alex Sadkin. They admired his work on several other recordings, notably a string of albums by Grace Jones. Talking Heads already knew how to densely layer up their music with arch, experimental sounds. They wanted someone who could help them strip some of that away to create more immediacy on their new album.

“We loved the clarity and punch that he got on those records, and we thought we would like to continue the kind of — whatever innovative kind of writing and recording stuff that we did but with his kinds of sounds,” Byrne said of Sadkin.

The material on Speaking in Tongues definitely leaps forward with intent. The album opens with “Burning Down the House,” which is built on amazing rhythms that Byrne meets with halting, driving vocals. The whole track is like a firmly drawn underline that accentuates the strangely unnerving lyrics: “Hold tight/ We’re in for nasty weather/ There has got to be a way/ Burning down the house.” The R&B and world music sounds that Talking Heads had been experimenting with are still present but with the added sleekness they sought. “Girlfriend Is Better” is a vibrant funk track, and “Pull Up the Roots” intertwines a steady groove with bendy beats and an undulating melody. The songs are complicated without being convoluted, a feat few of Talking Heads’ contemporaries could accomplish with quite the same panache. They were more determined than ever before to keep that control, writing out the chord structures for songs rather than just riffing until they found a song’s shape.

“Recording the music for our previous album, Remain in Light, it became clear that that a lack of chord changes made it challenging to write interesting melodies,” Harrison said. “There were limitations to where a melody could go.”

None of these alterations in approach meant Talking Heads were softening the blunter edges that were sometimes cited when sleuthing out why such a critically acclaimed act had such a difficult time breaking through to the masses. Speaking in Tongues is loaded up with cuts that rewarded the philistine-flouting faithful. “Slippery People” is all sleek abstractions, “I Get Wild / Wild Gravity” is itchy art rock, “Moon Rocks” swirls and swerves with exploratory jamming, and “Swamp” almost hits Frank Zappa levels of expertly rendered oddity. Byrne also counterbalanced any added approachability in the music with a strategic undoing of straightforward storytelling in the words. “Making Flippy Floppy” moves with percolating zest and sets the mind reeling with lyrics: “You don’t have to wait for more instructions/ No one makes a monkey out of me/ We’re lying on our backs, feet in the air/ Rest and relaxation, rocket to my brain.”

“On this record, I didn’t want to write linear, narrative lyrics,” Byrne told a reporter while making the rounds for the album. “Maybe next time I will, but on this one I wanted words to have the quality of dream images or mythical images — lyrics that don’t make sense in a literal way, but I would hope have emotional impact. They seem like highly resonant images that move people without having to think about what it’s about. And if you stop and try to figure out what’s being said, you get lost.”

The album closes with the striking lovely cut “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody).” The lyrics still have a obtuse quality (“Out of all those kinds of people/ You got a face with a view”), but there’s also a newfound willingness to include a discernible emotional vulnerability in what’s being expressed. Byrne sometimes referred to this as the first real love song he ever signed his name to, and there are moments when the lyrics are almost jarring in the directness of their feeling: “Home, is where I want to be/ But I guess I’m already there/ I come home, she lifted up her wings/ Guess that this must be the place.” Appropriately for a last track, it points to where the band went next.

The greater control Talking Heads took with the production of the album continued all the way to the finishing touches. That was at least true of Harrison, who had a rising interesting in producing material for other artists. He stuck around to finalize what they’d made together.

“When we did Speaking in Tongues, Alex Sadkin introduced me to Ted Jensen of Sterling Sound, who was the mastering engineer,” Harrison said later. “By the end of the record, everybody else had left town and I was the only one left, so I went and worked with Ted and finished it. From that point on, I was the one who mastered the records. Sometimes it is taking a long time to get the technical stuff right, but I was enough of a perfectionist that I wanted to do that.”

By most measures, Speaking in Tongues was a commercial breakthrough for Talking Heads. Its peak position of #15 on the Billboard album chart wasn’t that much higher than what its two studio predecessors mustered. Even so, it became the first Talking Heads album to move enough copies to earn a platinum certification, and “Burning Down the House” was a Top 10 hit, the only time the band crossed that significant threshold.

“I think the time is right,” Weymouth said when asked about the commercial success of the album. “And I think the attitude that we had in the studio when we were making the record really came through. We were very happy when we were recording this records, and that feeling is picked up in the instruments and in David’s vocals.”

In between Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues, Talking Heads followed the customary approach of all bands born in the nineteen-seventies that needed to keep their name familiar in a longer stretch between studio efforts: They released a double live album. For the tour for Speaking in Tongues, they came upon a yet more ambitious way of documenting their formidable skills in concert. In December 1983, director Jonathan Demme filmed four shows in Los Angeles. Around four months later, the film he made from that footage, Stop Making Sense, debuted at the San Francisco International Film Festival. An absolute masterpiece, Stop Making Sense remains the consensus pick for the greatest concert movie ever made, a verdict that only grew more certain and universally agreed upon with a recent rerelease.

“One of the things that I think Talking Heads stood for was sticking to your guns, doing what you did best, and where it took you and whatever success it brought you, then that’s what happened,” Harrison reflected many years later. “And I think that was inspiring to people.”

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.