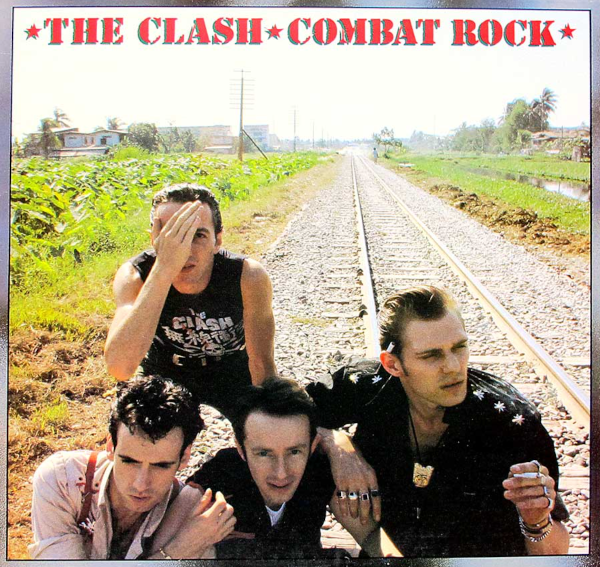

4. The Clash, Combat Rock (1982)

“This time we wanted to cut it down a bit,” said guitarist Mick Jones, who shared frontman duties in the Clash with Joe Strummer, of the band’s fifth studio album, Combat Rock. “It was a conscious decision on our part. We wanted to tailor it, jib it, make it a system as one. I think we mean to get across to a lot more people than we have in the past. We want to widen our listeners without being too preachy or trying to convert them. We want to be on the charts, but not like all the other big bands which leave people in the same state they were before.”

The Clash’s recent recording history at that time suggested that pruning their material was going to be more challenging than it might have been for other bands. They were coming off the massive Sandinista!, which was a triple album, and its immediate predecessor, London Calling, was a two record set. But the strategy of culling their output to a single LP proved effective for meeting the overall stated goal of audience expansion. Combat Rock became the most commercially successful entry in the Clash’s discography by a solid margin, especially in the U.S., where it was their only album to elbow its ways into the Billboard Top 10 and sold enough copies to earn double platinum status. Keeping with other band traditions, the process of getting to that point was highly fraught.

The longstanding poor relationship the Clash had with their record label, CBS, was at a new low point, thanks to a dispute over the pricing of Sandinista! that resulted in a compromise that severely cut into their earnings on the record. Seeking to right their tilting ship, the Clash looked to their original manager, Bernard Rhodes, who had parted ways with the group not longer before they started work on London Calling. He was reinstalled in that post and quickly got to work on a fresh renegotiation of the band’s contract with the label. A true believer in the Clash’s creative potency, Rhodes was the right person to be their ardent cheerleader and dogged advocate.

“The Clash represents hope, but we feel like it’s like trench warfare,” Rhodes proclaimed.

Giving the new album the working title Rat Patrol from Fort Bragg, the Clash started laying down tracks in London and then moved to Electric Lady Studios in New York City, where a good portion of Sandinista! was recorded. As usual, they had a surplus of songs, enough to fill another double album. The individual members also had strongly differing viewpoints about how the tracks should be mixed. Jones thought the songs should be longer and shaped into dance music. The rest of the band — Strummer, bassist Paul Simonon, and drummer Topper Headon — generally favored more compact, rock-driven mixes. Operating in that place of dispute was becoming the norm, and the Clash didn’t quite know how to break free of it. What was clear was that none of them could hammer what they had into a form that would earn consensus agreement.

“We were kind of falling apart, none of us were enjoying it,” Headon remembered. “It was about feel, we had to rescue that album. Mick tried mixing it, but it didn’t work. I even had a go at mixing it. Mick’s tried, Joe’s tried, and Paul didn’t wanna do it, so I did. Bless their hearts, love ‘em to death; there’s all three of them sitting behind me watching me trying to mix it. They’re all supporting me: ‘Come on, Tops!’ But every track ended up with all the faders up full.”

As the Clash struggled to bring the album to completion, CBS Records executives arrived at their customary stance of disliking what they heard. Judging mostly Jones’s mixes, the label bosses deemed the product unworkable as it was. This time, though, the Clash basically agreed, so they were amenable when Muff Winwood, a former member of the Spencer Davis Group who’d entered the CBS executive suite after a few years as an A&R man at Island Records, suggested that Glyn Johns be brought in to try his hand at a mix of the album.

Johns was a seasoned hand with more than fifteen years of experience as a producer, engineer, and mixer, including multiple stints behind the boards for the Who. After Johns listened to the different mixes the band attempted, he deemed them all indulgent. At the same time, he heard what he believed was the core of a compelling rock record. His first decree was that there’d be no more sprawl. This was going to be a single LP, and he was prepared to help the band be ruthless in cleaning up the clutter. He also walked headfirst into the brewing tensions within the band.

“I don’t think I’ve enjoyed working with anyone as much as I did with Joe Strummer, a lovely bloke and unbelievably talented,” Johns told Uncut many years later. “He and Mick had been in a New York studio for two weeks trying to mix the record and it hadn’t worked out, so Muff Winwood asked me to mix it. Although punk had never appealed to me, I was astounded by the music’s skill, ingenuity, and humor, and the quality of the lyrics. But it was a hell of a mess. I started with Joe at 10:00 a.m., and he was happy for me to get stuck in, edit, chuck stuff out. It was like fighting through the Burmese jungle with a machete. Then, at 7:00 p.m., Mick arrived, and I played him what we’d done. He sat there with a sullen expression and criticized everything. I said, ‘That’s a shame, but I’m afraid they’re done. You were supposed to be here at 10:00 a.m.’ He got pissed off and left. There was a big row the next day, then I just got on and finished it with Joe, who was very supportive. It was rather sad, but there are some classic performances on it and they would have been classics whether I’d mixed them or not.”

The album bearing Johns’s thumbprints was retitled Combat Rock, partially inspired by the bruising process to get it made. The name also reinforced that the Clash’s streamlining of their output and interested in achieving a more formidable chart presence didn’t mean they were steering away from the political engagement that energized earlier records.

“Most of the new pop doesn’t try to engage reality at all, which isn’t necessarily bad, because I like a lot of the new stuff too, like Human League” Jones observed. “But sometimes you have to get down to facing what the world’s about, and that’s not something all those party bands want to do. I don’t know. I mean, don’t get me wrong, we have our share of fun too, but these days, it’s just that all the parties seem so far away.”

The fundamental approach of the Clash is literally declared at the very beginning of the album Opening track “Know Your Rights” begins as Strummer announces, “This is a public service announcement/ With guitar!” Over a pulsing beat, Strummer then details the rights afforded to the citizenry, albeit delivered with cynical backspin: “Number three/ You have the right to free speech/ As long as/ You’re not dumb enough to actually try it.” Later, the gentle yet intense “Straight to Hell” (which M.I.A. would later sample to inspired effect on the hit “Paper Planes”) expounds on innocent people left abandoned, whether working-class Brits who watched helpless as their industries collapsed (“As railhead towns feel the steel mills rust”) or the children of U.S. servicemen left behind in Vietnam (“Wanna join in a chorus of the Amerasian blues/ When it’s Christmas out in Ho Chi Minh City/ Kiddie say, papa papa papa papa papa-san, take me home”). If there’s a blunt-instrument quality to their commentary, the Clash is at least sticking with their conviction of trying to say something more substantial in their songs.

Shaping Combat Rock to more palatable to the masses didn’t cause the Clash to entirely jettison their penchant for oddity. The crunching reggae cut “Red Angel Dragnet” features lead vocals by Simonon and includes friend of the band Kosmo Vinyl dropping in to recite Travis Bickle’s Taxi Driver monologue directed at the screwheads of the world. The drab tune “Ghetto Defendant” similarly makes room for Allen Ginsberg to murmur a narrative piece, and “Overpowered by Funk” strains to live up to its title as graffiti artist Futura contributes a flatfooted rap. The Clash ran afoul of copyright protections when they tried to enliven the tired-sounding “Inoculated City” with an audio sample from a 2000 Flushes commercial that they subsequently had to remove after the manufacturer complained. Whether any of these weird embellishments work is open to debate. For Strummer, every swipe at established boundaries was a means to staying relevant.

“To me, the reason the Sex Pistols died was that they weren’t writing any new songs,” Strummer told a reporter. “You can’t just do the same thing over and over and survive. But it also stimulates us to do things that we aren’t supposed to do musically, move into areas that are off limits for a rock band. We’d like to reach as many people as possible, but we also can’t resist the temptation of putting something we know is a little extreme on an album to see if the audience will be able to take it.”

It’s probably not reasonable to attribute any audience aversion to portions of Combat Rock on an unwillingness to embrace the Clash’s extremes. The album is filled with cuts that are not likely to find champions in any discussions of the best music the Clash had to offer. The inert “Atom Tan” and the listlessly lilting “Death Is a Star” come across as mere filler. “Sean Flynn” is a jazzy raga song about photojournalist Sean Flynn, the son of movie star Errol Flynn who was likely killed while on assignment during the Vietnam War. The track goes nowhere, drifting along as if in search of a structure that was denied it by the band. “Car Jamming” is the Clash’s attempt at shuffling R&B, and it comes across like the J. Geils Band trying on post-punk for a laugh.

There are two prime entrants in the Clash canon on the album. Built on a demo Headon laid down more or less on his own, “Rock the Casbah” was given a new set of lyrics written by Strummer, who drew inspiration from stories he read about individuals living in repressive Middle Eastern regimes who rebelliously played forbidden rock ‘n’ roll music. Thumping and kind of dumb (and ripe for misinterpretation by bigots who saw it as a blanket attack on all Middle Eastern people and culture), the song was a major hit for the band, logging time in the U.S. Top 10. It’s bettered significantly by “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” a fervent rock song electrified by a tight Mick Jones guitar riff and simple but affecting lyrics of relationship confusion (“One day it’s fine, and next it’s black/ So if you want me off your back/ Well, come on and let me know/ Should I stay, or should I go?”).

Even as Combat Rock was released to relatively quick success, the Clash remained in turmoil. When time came for the band to embark on a tour to support the album, Strummer was nowhere to be found. Evidently overwhelmed by his rising rock star status, he struck out on an incognito holiday in France without informing anyone of his whereabouts. Dozens of concert dates needed to be rescheduled. Then, less than a week after Strummer returned, Headon was ousted from the band because of the damaging effects of his heroin addiction. Terry Chimes, the Clash’s original drummer, was brought it to handle duties behind the kit for the tour. As an outsider, Chimes was well-equipped to see how the band’s bonds were fracturing under the pressure of their swelling fame and the discomfort of playing to audiences fortified with newcomers who didn’t really understand the band’s ethos.

“I don’t think I’ve experienced anything else quite like being with this group,” Chimes said at the time. “There’s a certain way in which, when people are in danger, they’ll pull together. Though the group is rarely in any real danger, the audience is a challenge. The group has to meet that challenge together, so it draws you closer. Of course, when you’re not on stage, you move apart again.”

From there, everything got worse for the Clash. Around a year after the release of Combat Rock, Strummer and Simonon teamed up to fire Jones from the band, fed up with his evident unwillingness to help them capitalize on the success of their hit album. There was only one more studio LP credited to the Clash, the dismal 1985 album Cut the Crap, before they disbanded for good. Rather than plodding along to diminishing returns, the Clash flamed out.

“I think what’s really interesting, in hindsight, that in some ways it’s probably a good thing that the band did start to sap each other,” Simonon later reflected . “I don’t think we could have continued. Reality was starting to leave us, because of the success and the environment that we were in, with this collection of people that suddenly were there to carry our bags and wash our socks.”

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.