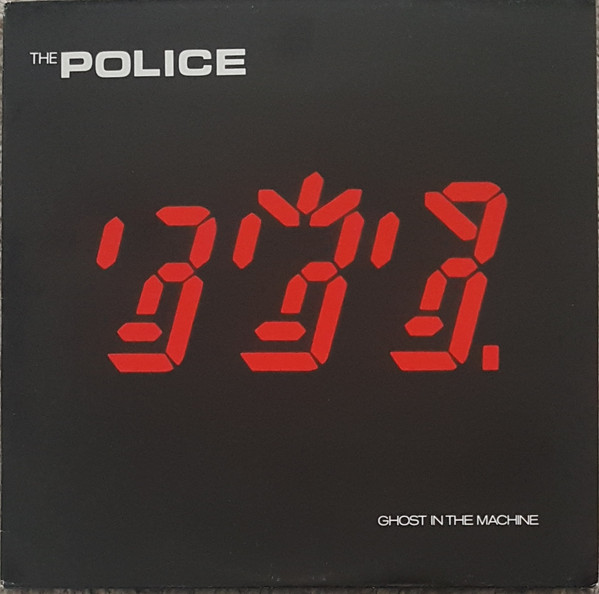

2. The Police, Ghost in the Machine (1981)

After constantly operating under the nettlesome, intrusive scrutiny of their record label, the Police were finally given the opportunity to record a new studio album on their own terms. The trio, comprised of bassist and lead singer Sting, guitarist Andy Summers, and drummer Stewart Copeland, had enjoyed commercial and critical success right their first LP, Outlandos d’Amour, released in 1978. Even so, the bosses at their label, A&M Records, always seemed to want a little more. They pressed the band to record new records at a rapid pace and peppered them with notes about adjustments that could be made to deliver bigger and bigger hits. When the Police’s third album, Zenyatta Mondatta, proved to be a breakthrough in the U.S. market, the band had the clout to dictate how they’d approach the follow-up. That album was Ghost in the Machine.

For starters, the Police gave themselves a little more time. Rather than racing to complete an album in a tight window between tours, they set aside a comparatively luxuriant six weeks to lay down their various tracks. After recording their first three albums in Europe — the first two at Surrey Sound, in the U.K., and the third at Wisseloord Studio, in the Netherlands — the Police headed to George Martin’s AIR Studios, happy that the remote Montserrat location of the facility meant they were far less likely to get unwanted visitors from the label. Finally, they made a significant change in who was behind the boards for them. Nigel Gray, who’d produced all the Police albums to that point, was out, and Hugh Padgham was in.

When Padgham was brought onboard, he was coming off of overseeing a hit record for Genesis and another for that band’s lead singer and drummer, Phil Collins. According to Padgham, he wasn’t given a mandate to coax the Police to similar chart heights. If the approach was casual, the producer did have a strong sense of how he might help the band reshape and expand their sound.

“We really just all rolled in there and made a record,” Padgham later recalled. “Having said that, from a production standpoint, I was very keen on developing Sting’s songs properly on tape, because, although I loved the Police before then, the first three albums sounded very raw to me. What I wanted to do with the Police, from the first minute I heard the songs we’d be working on, was to develop the music as 3D, almost like a movie, with respect to some of the textures we can put into the music, which is the way I’ve always looked at making records.”

To achieve what he wanted, Padgham was open to making some unorthodox moves. When he decided that Copeland’s percussion parts came across as too confined when recorded in the studio, the drummer’s kit was moved to the nearby living spaces (either the dining room or the living room, depending on who’s telling the story) and the microphone were run to it there. As for the other half of the rhythm section, Sting preferred playing his bass in the control room, sometimes with his instrument plugged directly into the board. As it happened, Sting was aligned with Padgham’s conviction that the music could have more layers to it. Sting wanted to continue what he saw as an already established progression from the Police’s rough and ready beginnings.

“The second was a little more involved, the third more involved than that,” Sting said of the Police’s albums when assessing how Ghost in the Machine was different than its predecessors. “I played saxophone, we used keyboards for the first time really, and I also did a choral effect with my voice. So, really, we’ve gone from being a very sparse group to being a richly textured group.”

For anyone who’d pogoed joyfully to those early, less-involved Police records, the expansiveness on Ghost in the Machine was evident enough that it might even have been a little jarring. Befitting its title, “Too Much Information” is radically overstuffed, with elements borrowed from dance music and jazz, and “Rehumanize Yourself” is a bouncy, punk-edged song defiantly disrupted by bleating saxophone. “Demolition Man,” a song Sting had given to Grace Jones and that the Police almost immediately reclaimed, is riddled with Jamaican dancehall flavor and careens along with a hard rock drive. Album opener “Spirits in the Material World” leans on those freshly introduced keyboards to bring an enlivening current of tension.

Migrating further away from that now-bygone sparseness wasn’t uniformly embraced by all three band members, though. Summers chafed against the extra elements, preferring the leaner, more aggressive sound of the early albums. To be fair, his dim view of the band’s artistic direction was likely colored by other troubles. Amidst the recording session, Summers’s wife called and informed him that she wanted a divorce, so that surely didn’t help his mood. Then there was the welling animosity among the three blokes in the band. There had been scraps before, but the Police also developed a strong sense of camaraderie as they mutually navigated their fast rise to fame. That sense of togetherness was always fragile, and it fell apart completely during the making of Ghost in the Machine. It wasn’t solely sonic considerations that had the Police recording their contributions in separate rooms.

By most accounts, a major accelerant to the band’s interpersonal woes was the egotistical isolationism of Sting. The reasonably egalitarian, collaborative approach of the Police’s early days was long gone. Sting brought a touch of dictatorial flair to the sharing of new songs he presented to the band, which left Summers and Copeland sometimes feeling like they were merely backing players to his rock star aspirations.

“After the first album, he’d reveal each new song on an as-needed basis, and in the recording studio,” Copeland recently told The New Yorker. “We didn’t get to rehearse them. I’d listen as he was showing Andy the chords. And I’d sort of tap it out on my knee. Okay, let’s do a take. Maybe do three takes. Use the second take. And, typically, that’s on the record forever, whatever I came up with in twenty minutes. The guitar, all the vocals, everything else, they redo it all. It’s finely crafted, tuned, and honed over months.”

Copeland took to referring to the frontman’s proclivity for bending every track to suit his own preferences as “Stingosis.” If Sting’s tendency for commandeering the creative process had been in place for a while, his most off-putting behaviors were exacerbated by drugs. Somewhere around this time, Sting became a regular user of cocaine.

“Sting was never really into drugs until being around coke,” Sonja Kristina, Copeland’s soon-to-be-wife at the time, told Mojo many years later. “It had a bad effect on his personality. It made him less considerate, therefore more prima donna-ish and tiresome.”

Sting later expressed regret over his treatment of Summers and Copeland at that time, accepting blame for at least some of the problems that beset the group. In the moment, though, he was very assured of the superiority of his artistry as he asserted his vision over theirs. Even as the other two-thirds of the Police tended to downplay internal band strife to music journalists, Sting seemed pretty content with banging pans and yelling, “I am so great.”

“I have to be careful not to trample all over them,” Sting said in an interview. “I can be very aggressive, only because I have an impassioned belief in my ability to write songs. I don’t believe in Andy or Stewart essentially as songwriters. They’ve written songs, but it’s not really their forte. They’re musicians. That’s a different kind of skill, involving a different part of the brain, actually.”

Sting’s dismissal of his bandmates’ songwriting ability was so thorough that he raised a fuss when A&M Records expressed interest in making the album’s first single the Summers-penned “Ωmegaman,” which was very much aligned with the immediate post–prog sound that was all over album rock radio in that era. Sting effectively vetoed the decision, and Ghost in the Machine was instead initially represented by the tingly, vibrant love song “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” in most territories. At home in the U.K., the first single was “Invisible Sun,” a song that resides in the aching anthem territory that U2 was just starting to stake out and was inspired by the ongoing unrest in Northern Ireland. Drawing his lyrics from such current events was something Sting was just starting to feel was part of his mandate.

“There’s a lot to accomplish, an awful lot, and as a musician, I have power,” Sting said when asked about the increasing infusion of political concerns in his lyrics. “Very limited power, but maybe more than the man in the street. God’s given me a knack, and I’m willing to stick it out occasionally.”

Ghost in the Machine ranges widely. Even when the materials isn’t as strong, it’s usually impressive to see the band try on different genre guises and have them all fit reasonably well. “Hungry for You (J’aurais toujours faim de toi)” is akin to the pop experimentation that Thomas Dolby was just getting up to, and it’s interesting enough to almost forgive the pretentiousness of the French lyrics. “One World (Not Three)” has a bracing reggae pump, and the Copeland composition “Darkness” traffics freely in fusion rock. “Secret Journey” is saddled with some truly dopey lyrics posing as profundity (“Upon a secret journey/ I met a holy man/ His blindness was his wisdom/ I’m such a lonely man”), but its music has a probing vastness that forecasts the most impressive artistic achievements that would be found on the Police’s next album, the blockbuster Synchronicity.

Ghost in the Machine was an impressive commercial performer in its own right. It was the Police’s third straight album to top the chart in the U.K., and it was their first to climb as high as the runner-up spot in the U.S. The album stayed at #2 on the Billboard album chart for six straight weeks, blocked from the top first by Foreigner’s 4 and then by AC/DC’s For Those About to Rock We Salute You. The Police embarked on a concert tour that lasted more than a year and entailed a hundred dates. Through it all, Sting’s sideline acting career and tales of band squabbles fueled persistent rumors that the Police were on the verge of breaking up.

“Well, the press does put things we say in big letters sometimes because they have to have some kind of headline, but it’s not that simple,” Summers said. “Any of us could say, ‘Right, I’m not playing another note with this group,’ but you don’t do that, you know? We have so much to gain from it, it would be ridiculous to stop. Maybe a day will come, but it’s not going to break up overnight. We’re contracted to make quite a few more records.”

No matter how many records were on that contract, the Police managed to make only one more before they were done, more or less for good. If there would be a finale, at least it was grand. The Police bowed out with the biggest album of their career.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.