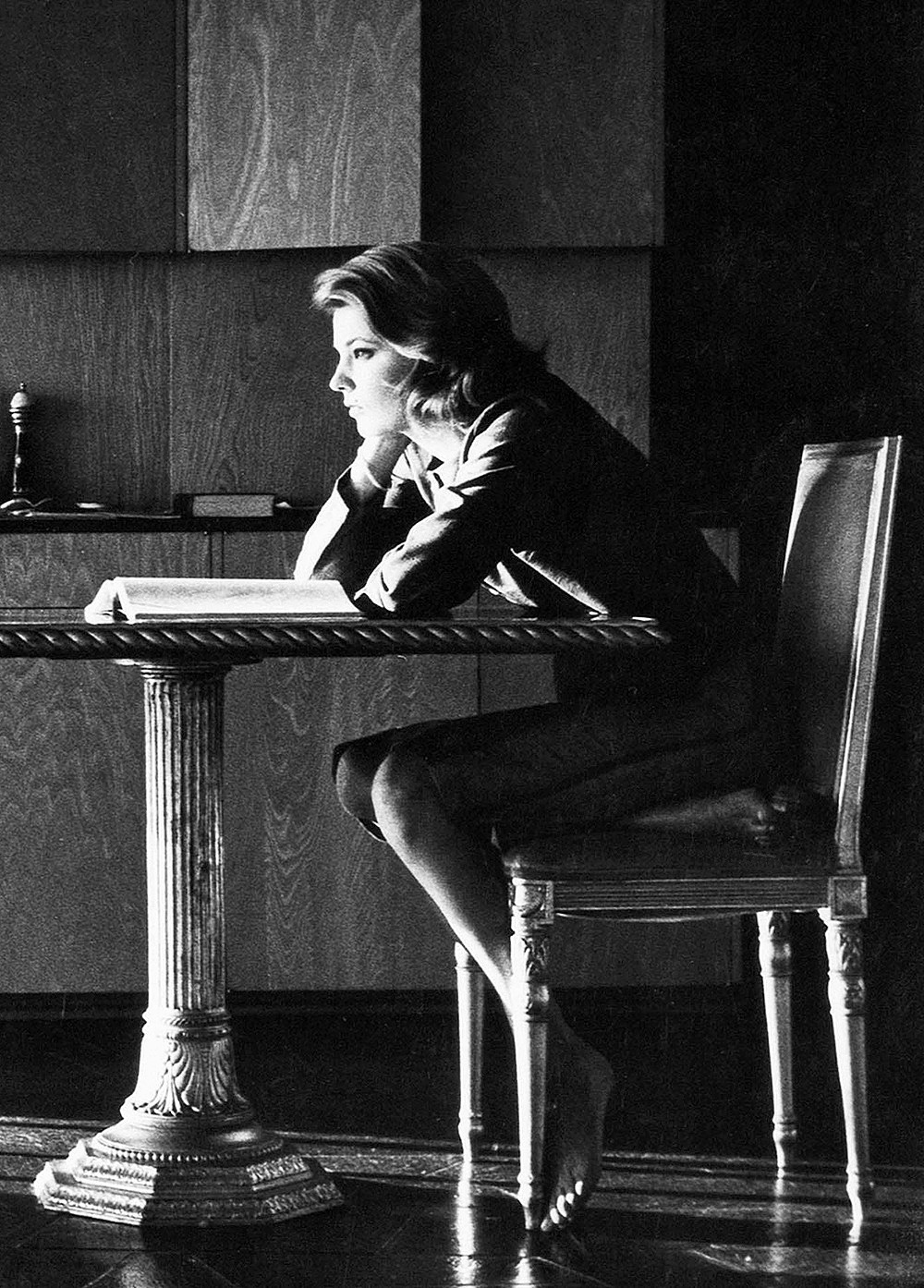

Gena Rowlands acted quite a bit before her husband John Cassavetes started directing movies that had prime roles for her. I wonder how many people saw the typhoon inside of her as she moved through guest roles in episodes of Laramie or The Tab Hunter Show or The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. Go back and watch any of those now, and it must be discernible, only because Rowland’s later work trained everyone what to look for: the fearlessness, the whip-smart invention, the crackling fire behind the eyes that signaled unpredictability. In her best work — and her very best work deserves a place in any conversation about the finest acting ever committed to film — Rowlands is deeply naturalistic and still willing to make big, bold choices that should disrupt the grounded reality of the performance. Instead, the brash folds in to the subtle to create a portrayal that cements the truth of the entire film around her. There are other strong performances in the films that Rowlands commands, but those fellow actors are clearly beholden to what she is doing. Rowlands controls their tides.

Cassavetes saw the typhoon inside his wife. He wrote her parts of ferocious intensity and gave her the space to make magic happen within them. No one else was doing that. The same year A Woman Under the Influence was released, Rowlands’s other screen credit was an episode of Marcus Welby, M.D. Anyone looking for a single film to illustrate how powerful and wonderful acting would be advised to start with A Woman Under the Influence, and they’d be okay if the considered their survey complete and the selection process done at that point, too. Rowlands unerringly credited the quality of the script for her performance, but that implies that any other actress could have stepped into the role of Mabel Longhetti, a housewife driven to unsettling behavior by loneliness and the pressures of her life. It’s unimaginable the anyone else could achieve what Rowlands does in the role. She is towering and intimate at once, making every last minuscule moment of her time on screen count.

Rowlands gave performances of this caliber time and time again when she was collaborating with Cassavetes. She’s not wrong to say that he wrote her tremendous parts, but it took her to embody them. She wasn’t some passive beneficiary of his creative daring. He wrote them because she was there. Myrtle Gordon, the lead role in the 1979 film Opening Night, is a decadent feast of actorly possibilities. She’s an stage actress driven to the edge of desperation by a floundering career and struggling to connect to her character in a new play. She’s cracking up and drinking heavily, slipping into other guises in her real life in some misguided attempt to rediscover herself. And she’s carrying long-festering guilt about a youthful accident and seeing ghosts. A tour de force is the bare minimum required of the role. Only Rowlands could make that level of complicated, high-wire acting her baseline and somehow get more staggeringly impressive from there.

After Cassavetes died, in 1989, and Rowlands had to settle for move roles crafted for mere mortals, I think her strength and flashpoint energy were still discernible. In simpler turns in the likes of Once Around, Something to Talk About, and She’s So Lovely, Rowlands steps forward in her handful of scenes and briefly claims the hard-earned right to be the most interesting person on the screen. In those smaller jobs, I sometimes feel like I can see her command a moment and then lean back satisfied and ready to be met on the terms she’s laid out, like she’s saying to her fellow actors, “Now you try.” It’s not a challenge; Rowlands clearly didn’t operate with that kind of ego. Instead, it’s an invitation. Come on in, the water’s wild and rough. In acting, that’s better than placid safety any day.

Pedro Almodóvar dedicated his marvelous 1999 film, All About My Mother, in part to Rowlands. He had never worked with her, never met her. Almodóvar simply saw Rowlands as once of those rare performances who has disparate strengths working in tandem. In an interview, Almodóvar expounded on classic actresses who moved him, citing Greta Garbo’s fortitude and Elizabeth Taylor’s fury in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, “that mixture of being open and torn apart, with style and guts.” Almodóvar continued: “The mixing of the guts of Taylor with the spine of Garbo is very interesting. I don’t know if she’s successful now, but in America you have a wonderful actress who also mixes these two things in very sincere and passionate acting: Gene Rowlands.”

Guts and spine. Very sincere and passionate acting. That looks right to me.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.