In the Heat of the Night was a bestseller, and its direct confrontation of the ongoing bigotry in a certain part of the nation’s geography made it especially well-suited for director Norman Jewison’s determination to address weightier topics after a string of more frivolous features to start his Hollywood career. He’d just guided the Cold War satire The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming all the way to an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture and three other Oscar nods, including one for Alan Arkin in the category for lead actors. As a follow-up, he worked with producer Walter Mirisch and screenwriter Stirling Silliphant on the screen adaptation of the 1965 novel about a Black police detective who ventures into the hostile territory of the U.S. South to investigate a murder.

There was little question about who was the best choice to playing the visiting homicide investigator, who was named Virgil but notably reminded at least one person that he was more commonly addressed as Mr. Tibbs. Among Black actors, Sidney Poitier was the preeminent star in the movie business, and the Academy Award on his trophy shelf was further argument that he was the performer best suited to take on such formidable material. Recollections differ on how Rod Steiger was brought in to play Bill Gillespie, the Mississippi police chief who grudgingly plays host to Detective Tibbs. Supposedly, Jewison’s first choice was George C. Scott. When he wasn’t available, the role went to Rod Steiger, and some suggested he was next on the wish list because a long acquaintance with Poitier that had included a wish to work together.

The character of Bill Gillespie was slightly reworked from how he appeared in the original novel, the filmmakers leaning into Southern stereotype. To complete the vision as he saw it, Jewison asked Steiger to chomp on chewing gum throughout his performance. Steiger rejected the idea at first, but Jewison persisted. The director asked Steiger to try it for just one day. To Steiger’s surprise, the simple choice was transformative. He instinctually adjusted the rhythm of his acting to match the working of his jaw on the gum. It became a tool for him to adjust the pace and beats of the performance. Having something that physical to key in on suited Steiger’s Method-actor dedication. By unofficial count, his work on the film required more than two hundred fifty packs of gum.

By homing on in the character’s rhythms, Steiger found ways to subtly alter it in key moments. Much as Gillespie presents as an archetype of Southern cruelly misdirected authority, Steiger undercuts it with an almost thoughtfulness that almost comes across as reluctant, as if it’s occurring against the character’s will. He sizes up moments as much as he reacts to them. It’s intricate acting.

In the Heat of the Night proved to be a formidable contender on Oscar night, which just so happened to be a ceremony that was postponed by a few days in somber response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In a year with two instant counterculture classics, Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, also in contention, Jewison’s police drama steeped in social commentary walked away with a Best Picture win and four other trophies. One of those went to Steiger, who lauded Poitier for educating him on matters related to racial prejudice in the U.S. Steiger capped his acceptance speech by reciting the well-known slogan of the Civil Rights movement “We shall overcome.”

The compass of Jewison’s career was now calibrated, at least as far as public perception went. No matter what he did subsequently, the proper Jewison pictures were those that addresses social injustice in some way. The films that had import. His next invitation to attend the Oscars might have been for a musical, but the film in question was the culturally potent screen adaptation of Fiddler on the Roof (which nabbed acting nominations for Topol and Leonard Frey). Jewison alternating between more diverting fare and message-heavy dramas. For every Rollerball, there was an And Justice for All. Best Friends, a romantic comedy pairing Burt Reynolds and Goldie Hawn, was quickly followed by A Soldier’s Story, which seemed genetically designed to attract Academy Awards attention. The next time actors were obligated to thank Jewison from the Oscar stage, it was for one of the films that, on the surface, seemed like one of Jewison’s larks.

John Patrick Shanley had a few stage plays and one produced screenplay to his credit when Jewison optioned a new script titled The Bride and the Wolf. One of the first things Jewison said to Shanley when the first met was that the title was horrible. It sounded like it belonged on a horror film instead of what Shanley wrote, which was a wistful, sometimes bittersweet story of a complicated affair between two people and the sprawling Italians families around them. Asked to come up with a new title, Shanley presented Jewison with a long list, and the two agreed that one of the options was clearly better than the others. By the time Jewison started shooting, the film was called Moonstruck.

The reluctance Jewison once faced when making suggestions to Steiger almost two decades earlier was repeated tenfold with the stars he enlisted for Moonstruck. The star-crossed lovers were played by Cher and Nicolas Cage, and both were entirely resistant to Jewison’s suggestions, so much so that he confided to other on set that he’d never before faced such difficulty when directing performers. Maybe in part because of that, Jewison employed every method he could think of to get scenes shaped the way he wanted them. For a major scene at the end of the movie, where many of the principal players come together for an emotionally fraught exchange around a kitchen table, Jewison told the crew to take an extended break, and he took the cast through a rigorous rehearsal process that would have been more common for a stage work. Only after he was satisfied that the actors had the rhythm of the scene down did Jewison figure out how he would place the cameras to film it. The grueling process earned Jewison a punitive fine from the Screen Actors Guild because he blew past the performers’ promised meal break.

The challenges Jewison faced in working with Cage and Cher — both still in their first decade of film work — were countered by a supporting cast stocked with veteran character actors. Later, Jewison said that Olympia Dukakis, enlisted to play the mother of Cher’s character, was one of his most consistent champions and a steadying force on the set. Dukakis wasn’t the first choice for the role. Oscar-winning actresses Anne Bancroft and Maureen Stapleton were both ahead of her on the wish list, but they were judged to be too expensive for the modestly budgeted feature. Casting director Howard Feuer remembered Dukakis from previous projects and brought her in to read for Jewison. He hired her on the spot.

If Cher and Dukakis came at the roles — and their relationship with Jewison’s directing — from different angles, they both strike a similar tenor of highly emotive acting as an entry point to wisely, warmly plumbing the emotions of their characters. The stereotype of effusive Italians is undoubtedly present, and yet the performances unearth the human complexities coexisting within the broad demonstrativeness.

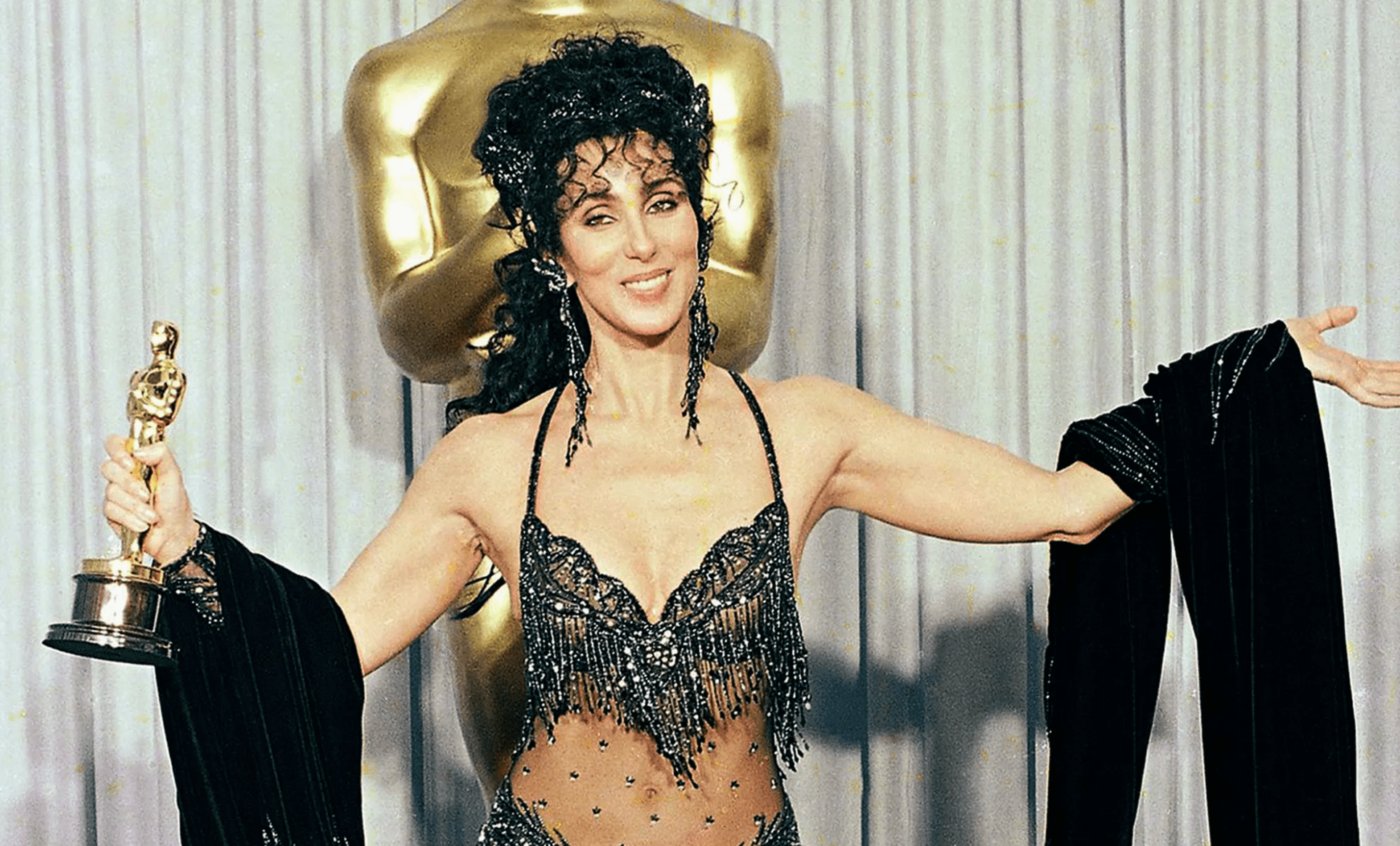

At times during the production, Cher confided in Dukakis misgiving about her own performance and certainty that the movie would bomb. She was wrong on both counts. Moonstruck was a steadily box office hit upon its release in late 1987, and it’s gone on to be one of the more beloved classics of its era. As for Cher’s performance, Academy voters made a persuasive argument in its favor. Both Cher and Dukakis took home Oscar statuettes for their work in the film.

To find about more about the premise of this series, check out the introduction. For other entries, click on the Actors Director tag.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.