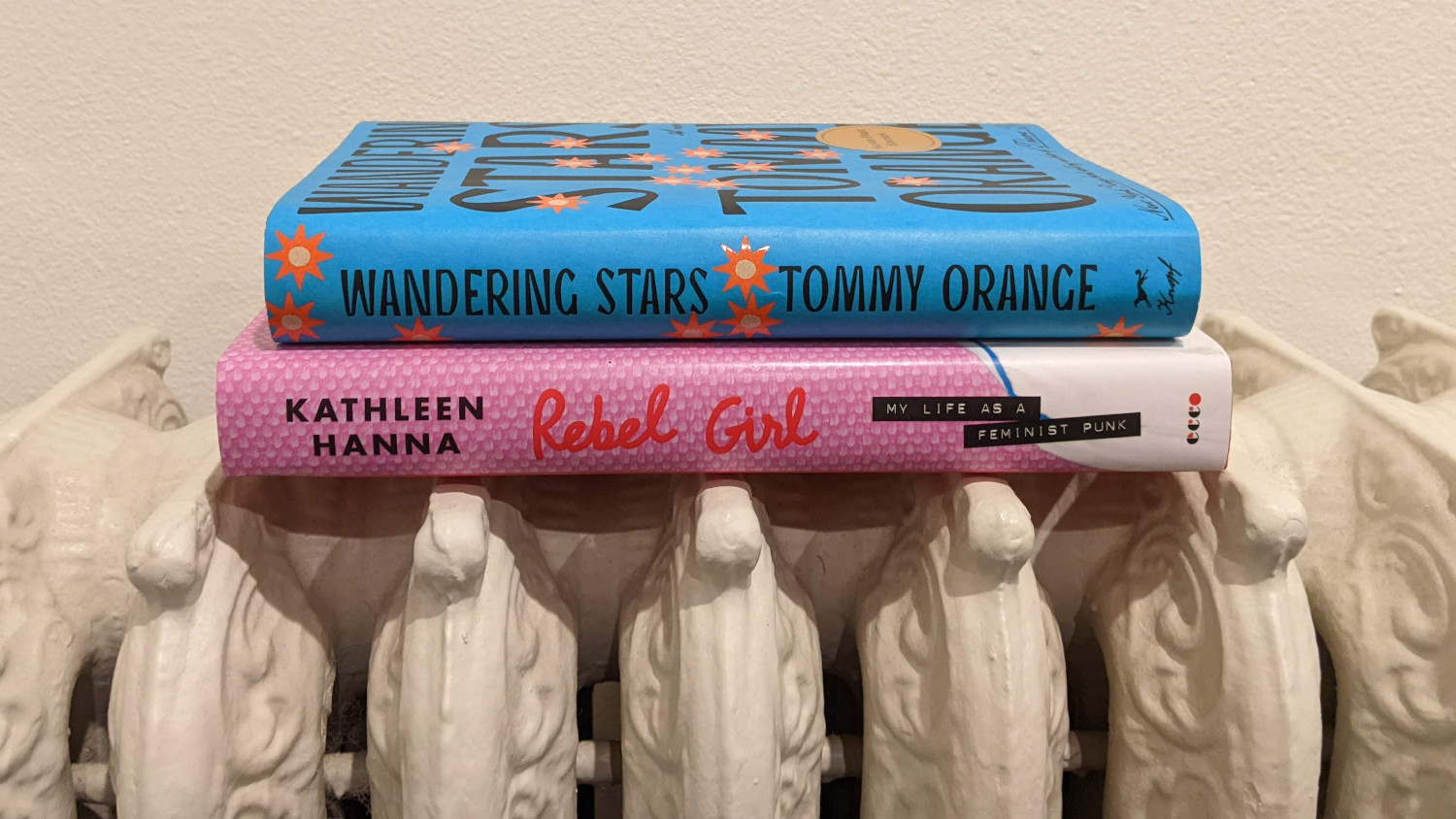

Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

Fiction, 2024

As for me, I came into this world without a name. Didn’t even cry or hardly make a sound for years. Quiet as a stone was what my mother told me once I was named Opal and old enough to ask her why. It’s this stone, she said, and put her hand to her heart. I thought she meant her heart was a stone, but she pulled out the stone for me to see, the one I was named after, it was the only time I ever saw it. It seemed to me that every color in existence was in that stone, but it also looked mostly blue, moon and starlight blue you only see on certain nights. I asked her if I could hold it and she said no, plain as if I asked her if she could give me the sun.

Tommy Orange’s follow-up to his tremendous 2018 novel, There There, is an extension of that earlier work. The back half of Wandering Stars takes place after the shattering event that closes its predecessor, following some of the same characters as they edge through the aftermath of their experience. In this portion of the novel, Orange’s writing and perspective are familiar. He’s still examining the existence of Indigenous Americans living in urban settings in the here and now, doing so with precision and power.

The front of the book is more of a shift and, in my view, more vital. Orange spends the first half tracing the familial and cultural history that brought his characters to where they were at the beginning of There There. Because of the nature of that history, the storytelling is far from cutesy prequel material. With compelling force, Orange lays plain the generational trauma inflicted on citizens who are truly native to this land, whether militaristic massacres of whole camps or the cruel forced assimilation of boarding schools that were more like prisons for kidnapped children. The fiction Orange crafts is harrowing and enriching at the same time.

Rebel Girl by Kathleen Hanna

Nonfiction, 2024

I handed out about fifty flyers to the high school girls and left knowing I’d made the most of an hour I could have blown reading magazines. So much of my life I’d been numb, checked out, hiding from my dad, hiding from the sexist men in cafés, hiding from guys I’d rejected, hiding from my own feelings. That day reminded me that I wasn’t gonna let life happen to me anymore. I was gonna make things happen.

Kathleen Hanna is characteristically blunt and ferocious in her memoir, Rebel Girl. Thank the goddesses for that. The musician is likely still best known as the frontwoman for nineteen-nineties punk band Bikini Kill and the sometimes reluctant face of the riot grrrl movement that she helped flare to life around that time, and that part of her life gets ample attention in the book. Thankfully, Hanna is sure to give equal time to her other creative pursuits, including her visual art and later musical acts the Julie Ruin and Le Tigre.

The chapters are short and explosive as punk songs, making the book move at the speed of thought. That approach heightens the impact of Hanna’s admirably unguarded writing about the abuse she’s faced in her life and the way the associated trauma resonates for years, even decades. If the writing is sometimes unpolished, that’s a deliberate choice, too. Hanna doesn’t equivocate. She puts her whole, truest self forward. Music journalists always wanted to define Hanna narrowly, and this book serves as a revived pushback to that diminishing compartmentalization.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.