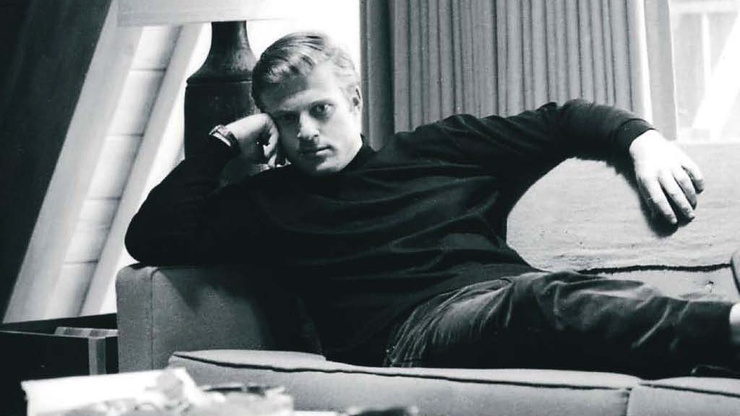

For my entire life, Robert Redford has been the pure definition of a movie star. He’s the exemplar, the epitome of that elusive, seemingly impossible figure who absolutely commands the screen just by being on it. That power was evident from his introductory moment in the 1965 film Inside Daisy Clover, not his first screen outing but the one that raised his Hollywood prominence enough to win him a Golden Globe in the category Most Promising Newcomer – Male. In the scene, Natalie Wood walks into a lavish bedroom and suddenly spins her head to left, the camera panning to take in the same sight as her: Redford in a rumpled-yet-still-impeccable tuxedo sprawled atop the silk sheets of the bed, somehow towering in repose and simultaneously completely relaxed and as ready to pounce as the most hungrily alert jungle cat.

It’s the ease of Redford in that moment that was his most distinctive quality. It was almost singular, except that it was a throwback to the generation of screen actors before his, before the studied realism of the likes of Marlon Brando and Redford’s pal Paul Newman took over. Because of this, I can’t help but think of Redford as the person who deserves the designation The Last Movie Star that is occasionally attached loosely to, say, Will Smith or Tom Cruise. Those actors are major names to be sure, but they work incredibly hard on screen, even when they’re supposed to be playing it cool. The only actor who came after Redford who approaches his casual comfort before the lens is Brad Pitt, who was notably cast by Redford in his 1992 directorial effort, A River Runs Through It, in the flawed golden boy role that must have felt very familiar to the star of The Way We Were and The Candidate. And yet the vast distance between two becomes apparent in their 2001 co-starring effort, the middling thriller Spy Game, that features Redford moving through scenes with the equivalent of merely piqued curiosity and Pitt anxiously asserting himself. Redford steals the movie.

It seemed Redford didn’t really want to be this sort of actor, though. He longed for prickly, problematic character parts. To his credit, he did constantly strive to wedge troublesome elements into roles that Hollywood power barons surely wished he would play with little more than a handsome gleam, whether Sonny Steele in The Electric Horseman, conman Johnny Hooker in The Sting (which earned Redford his only Oscar nomination for acting), or the title roles of Jeremiah Johnson and Brubaker. Even so, he was never going to be able to disappear into a role, and some character experiences were clearly beyond his reckoning. He coveted the lead in The Graduate, directed by Mike Nichols, who had worked with Redford on the hit Broadway stage production of Barefoot in the Park. Nichols quickly decided Redford wasn’t right for the role and told him so. Mark Harris included a fantastic story about this incident in his exemplary biography of Nichols:

Afterward, Redford went over to Nichols’s rented house in Beverly Hills and got the bad news over a game of pool. “You can’t play a loser,” Nichols said. “Look at you. How many times have you struck out with a woman?”

“And he said, I swear to you, ‘What do you mean?’ said Nichols. “He didn’t even understand the concept.”

If Redford had stopped at acting, he’d still be an important, beloved figure in U.S. cinema history. Instead, he proved to be an uncommonly good director, signing his name to several challenging, fascinating works, including the flat-out classics Ordinary People (which earned him an Academy Award for directing) and Quiz Show. He also regularly leveraged his celebrity clout to bolster film projects of great social value. He used his own money to buy the screen rights to All the President’s Men and was so central to its development process that he probably should have gotten a producer credit on the exceptional film that resulted. He lent his voice to Michael Apted’s powerful documentary Incident at Oglala and even recently served as executive producer for the television series Dark Winds, a too-rare showcase for Native American actors.

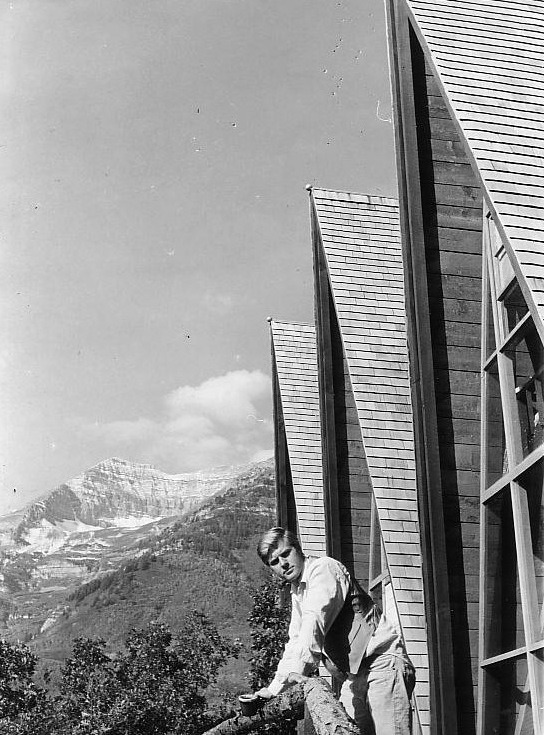

There’s no doubt, though, of Redford’s most significant legacy. The Sundance Institute and the film festival that shares it name transformed modern movies. When I was reviewing movies on a weekly basis for my college radio station, in the early nineteen-nineties, Sundance was a sort of Avalon of cinema to me, a promised land where everything I valued in the art I consumed — integrity, daring, invention — mattered above all, or at least above the skittish calculation practiced by major studios. As sequels and recycled familiar properties proliferated at the expense of original films in mainstream multiplexes, Sundance was promise and proof that there will still creators who committed themselves to art that challenged in some way. The one time I visited Park City, Utah, well outside of the timeframe when the vaunted film festival took place, just walking the streets felt like a semi-religious experience for me, as if there was mystical power in the geographical space where the likes of sex, lies, and videotape and Hoop Dreams first flickered to life before an audience. When the world shifted in such a way that I could experience a long-distance version of the Sundance Film Festival, it felt like fulfilling a nearly forgotten promise to myself. All the while, I was aware that Redford was directly responsible for this cherished part of my moviegoing life.

“Do you know what I learned from Utah, from living my life as I have?” Redford told a reporter a few years after the Sundance Institute opened. “That you only keep things if you’re willing to take risks – that you should make the best use you can of places and time, because with a certain success, a certain refinement in your life, you lose the very thing you started with, or you think you stand to lose it because the stakes are so high. . . so you try nothing new.”

Redford tried new things. Maybe more valuably, he devoted himself to ensuring the other people could try and experience new things, too.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.