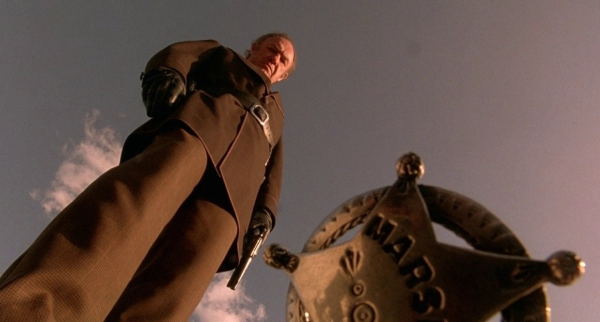

The Quick and the Dead (Sam Raimi, 1995). In the Wild West, a tough frontier town is ruled by a cruel mayor (Gene Hackman, basically giving a nastier spin to the Will Munny character a couple years after Unforgiven) who occasionally reasserts his authority by staging a gunfight contest in the thoroughfare. It’s March Madness with bullet wounds. The screenplay, credited to Simon Moore, lassos an array of colorful gunslingers into this scenario and so joyfully plays with Hollywood Western iconography that key characters are largely referred to as The Lady (Sharon Stone) and The Kid (Leonardo DiCaprio). Director Sam Raimi absolutely revels in the opportunity he has to make a hyperactive version of nineteen-fifties matinee movie for rambunctious boys. There are chunks of the script that simply don’t add up, and Stone never really gets a handle on her conflicted, vengeance-fueled character. Still, it’s fun to watch director Sam Raimi go wild with stylistic flourishes. He treats every showdown as a chance to construct a wildly inventive bit of visual framing. All of the crafts elements of The Quick and the Dead— the costumes, the sets, Alan Silvestri’s whip-cracking score — are downright ravishing.

It Felt Like Love (Eliza Hittman, 2013). The debut feature from writer-director Eliza Hittman is a tough, harrowing watch. A unblinkingly truthful coming-of-age drama, It Felt Like Love follows Lila (Gina Piersanti), a fourteen-year-old girl who lives in Brooklyn with her overmatched father (Kevin Anthony Ryan). She spends her summer trying to keep up with her friend (Giovanna Salimeni) who has more experience with boys, or at least adopts a persona that’s more sexually confident. Hittman is uncomfortably intimate in depicting what it’s like for an adolescent girl to play at being a grownup. Piersanti is a quiet marvel in the lead role, subtly conveying the ways Lila agonizes over her choices as she edges deeper and deeper into dangerous territories with people who are all too willing to take advantage of her. It’s a horror movie where the monster is the wounded neediness of youth.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953). Four years after Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was a sizable success on Broadway, it reached the screen as a big, colorful joint star vehicle for Jane Russell and an ascendent Marilyn Monroe. They play showgirls who are man crazy, albeit with differing opinions about the importance of bankbook size. The plot’s shaky, and Howard Hawks’s direction is uncharacteristically indifferent. Even so, there’s enough snap and sparkle to make this comedy work more often than it doesn’t, largely because of the performances of the two leads. Jane Russell is especially good at cracking off sharp comic lines. Most of the musical numbers are drab, whether the Jule Styne and Leo Robin tunes brought over from the original stage version or the new ones whipped up for the film by Hoagy Carmichael and Harold Adamson. The exception is “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.” Monroe is wildly charismatic in performing it, and the visual construction of it is dazzling. It’s a stunner of a scene, fully deserving its iconic status.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.