#31 — The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

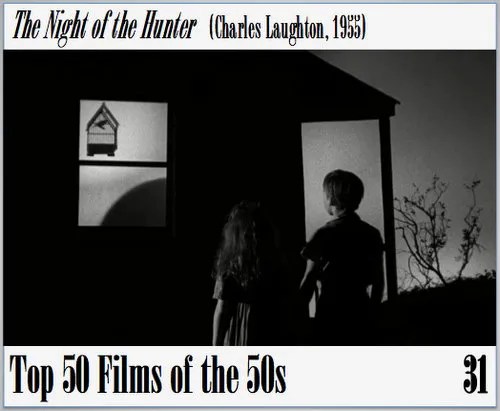

The Night of the Hunter is famously the only film directed by esteemed character actor Charles Laughton. I’ve also seen it cited more than once as the finest film ever directed by someone whose main gig was on the other side of the camera. It’s absolutely one of the most striking and distinctive such efforts, especially for its time. In adapting the bestselling novel by Davis Grubb, first published in 1953, Laughton and his collaborators made a grim, expressionistic work, one that veered away from the growing trend towards tenderized reality by basking in stylized artifice, finding deeper, darker truths embedded in the story in the process. The imagery in it is dramatic, potent, carved by shadows. Nightmares aspire to be this dark.

Robert Mitchum plays Reverend Harry Powell, a serial killer with “LOVE” and “HATE” tattooed across his knuckles. In his warped mind, he believes he is following the dictates of God Almighty by ridding the world of the sinful women he stalks. The motivation that drives the plot is based on a different sinful impulse: greed. Harry is cellmates with a bank robber (Peter Graves) whose latest ill-gotten gains weren’t recovered before he was tossed in jail. Harry makes the correct determination that the robber’s two children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce), know the whereabout of the loot. When Harry is released, he heads straight for the fatherless household with an eye towards enriching himself, using his well-honed tactics of terrorizing the defenseless in an attempt to ascertain where the treasure lies. The film’s stark, jagged visuals play out as a reflection of the shared perception of the beset children, like a school play gone horribly wrong. They naturally see the world in simpler terms–as clearcut as the opposites inked onto Harry’s fingers–and the film mirrors that, thanks in no small part to the bold cinematography by Stanley Cortez.

By all accounts, Laughton was a generous collaborator. Several of the crew members attested to his conviction to see them as fellow artists, all dedicated to the task of making this troubling material into true art. It makes sense that he would be highly attuned to the needs of the actors, all of whom prosper, especially Mitchum, chillingly comfortable in his overwhelming menace. It’s perhaps less intuitive that his care for all facets of the production would be so clear, except that he obviously had a vision that he wanted to bring to the screen, a vision that was just far enough outside of the norm that he needed every bit of focus and shared control to realize it. The fullness of his artistic instinct makes it all the more lamentable that The Night of the Hunter is the totality of his film directing career. There are indications that he intended to pursue other projects, but the chilly reception to the film, both critically and commercially, evidently brought and end to that. (Laughton had begun work on an adaptation of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead which he promptly abandoned after seeing the box office figures.) Intriguing as it may be to speculate on what else Laughton may have created, there’s an added power to The Night of the Hunter standing on its own. It suggests that a vision this singular couldn’t reasonably be extended beyond the frames of one film.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.