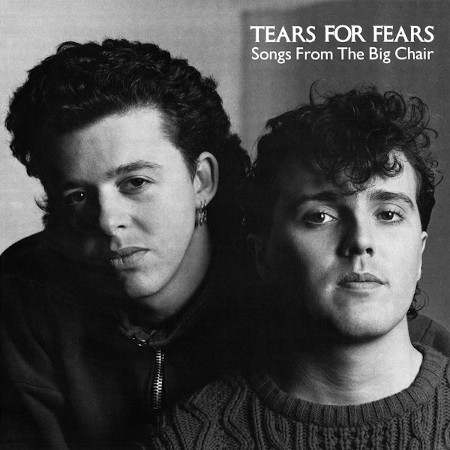

24. Tears for Fears, Songs from the Big Chair (1985)

Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith were angry at themselves for compromising. Tears for Fears, the band led by the longtime friends from Bath, England, delivered a major hit with their debut album, The Hurting, at least in their homeland. The album topped the U.K. charts and pushed three singles into the Top 5. Meticulous and deliberate in their craft first and foremost, the duo wasn’t ready to create new music in the immediate wake of that album’s success, but the record company held the strong opinion that the marketplace needed more. Orzabal and Smith enlisted the other band members, drummer Manny Elias and keyboardist Ian Stanley, in the writing of a new song while still on tour in support of The Hurting, and that collaboration, titled “The Way You Are,” was recorded and released as a single shortly after getting off the road. Compared to its predecessors, the single tanked, and Orzabal and Smith never relented in their assessment that it represented a dismal artistic failure. For their next album, they were determined to realize their vision without acquiescing to anyone.

From the outset, they found it was easier to assert themselves because of a change of personnel in the studio. They once again worked with producer Chris Hughes, who presided over The Hurting, but took advantage of a rift that developed between him and engineer Ross Cullum during the making of the Wang Chung album Points on the Curve. Orzabal in particular was weary of pushing back against what he perceived as the united front between Hughes and Cullum and was eager to bring in a different engineer who might be more amenable to the preferences of the band. Dave Bascombe got the job.

“Looking back now, I was Roland’s ally because when you got down to the nitty-gritty, I agreed with Roland a lot of the time,” Bascombe reflected many years later. “Obviously Chris was steering us in this commercial direction, which I wasn’t that keen on, and I don’t think Roland really was.”

As for what Orzabal and Smith were keen on, it was expanding the power and potency of the band’s material. In addition to the indignity of the dashed-off single that they loathed, the group was smarting from rough treatment from the British music press. As The Hurting grew in popularity, critics and other music journalists eagerly hurled barbs at the band, dismissing their songs as pretentious. In a sly, snide retort to that journalistic derision, Tears for Fears selected a title for their sophomore LP that referenced a plot detail in the 1976 TV movie Sybil. The traumatized title character, played by Sally Field, only felt safe when sitting on an oversized piece of furniture in her therapist’s office, hence Songs from the Big Chair. Aside from that inside jibs, Tears for Fears also labored to make their new album resoundingly clear in expression and intention.

“It was a conscious decision to go into the studio and turn out a bigger-sounding album, but it was unconscious, too,” Smith explained at the time. “We knew we wanted to make the music even more emotive than the first album. You’ve really got to hit people over the head with a block of wood to make them listen.”

The album opens with exactly that sort of large-scale hammering at a point. “Shout” is six and a half minutes of probing synths, blasts of droning guitar, and a tingly, insistent rhythm. The lyrics are simple to the point of mantra-like, particularly on the chorus: “Shout/ Shout/ Let it all out/ These are the things I can do without/ Come on/ I’m talking to you.” Orzabal maintains that the lyrics are largely about political protest, but the band’s reputation muddied external evaluation enough that many believe it to be inspired by primal scream therapy. Mild misinterpretation aside, the cut has a fervency that grabs the listener by the metaphorical collar, which is a suitable precursor to all that follows.

Not that everything that follows has the some tone or intensity. Songs from the Big Chair is fascinating because of how varied it is while staying within the musical mode established by Tears for Fears. “I Believe” has the sleek jazziness of lounge music, and “Mothers Talk,” released as a single around six months before the album’s release, has a clean, elegant dance music glimmer that almost suggests Madonna’s offerings from the same era. Most of the second side is given over to a small suite of songs that keep circling back on themselves, with the fusion rock scorcher “Broken” and yearning, tender pop number “Head Over Heels” most clearly intertwined.

Tears for Fears aspired to create Songs from the Big Chair with a less arduous approach than was taken with The Hurting. They recorded in a home studio and cultivated a looser environment with friends dropping by to hang out and listen to the latest tracks. Even so, it was still enough of a grind that it took about a year to complete the album, an expanse of time lengthened by the fact that they simply didn’t have that many new songs, necessitating occasional breaks to allow Orzabal and Smith to develop new material. That process sometimes led to fragments that they continued to tinker with when returning to the studio, sometimes reluctantly. One of those proved to be the album’s standout track.

“It was originally called “Everybody Wants to Go to War, which I knew didn’t work,” Orzabal said many years later. “My wife Caroline loved it, but when you’re a songwriter who doesn’t like the lyric, the song dies. It was our producer Chris Hughes who championed ‘Everybody.’ It got to the point where, at 6:00 p.m. at the end of every session, he’d make us spend an hour going over and over it. That’s where I came up with the guitar figure and changing it to ‘Rule the World,’ which is when I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s good.'”

Sleek, urgent, and strangely poignant, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” arguably was and still is the most resonant song from the album. It sounds enormous and restrained at the same time, and the simple, cynical truth of the title makes the lyrics feel more profound than they really are (“There’s a room where the light won’t find you/ Holding hands while the walls come tumbling down/ When they do, I’ll be right behind you”), which is its own type of grand rock ‘n’ roll art. Like “Shout” before it, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” was a chart-topper around the globe. In the U.S. and other place, the album reached the same apex on the album chart. Tears for Fears made exactly the album they wanted to make and were rewarded by becoming, for the moment anyway, one of the most popular bands in the world.

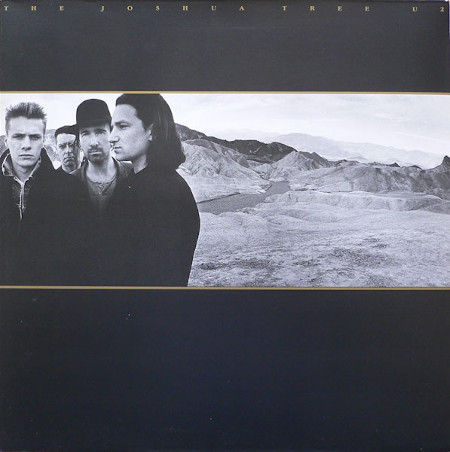

23. U2, The Joshua Tree (1987)

“With Joshua Tree, we wanted to make a really great record, with really great songs,” U2’s guitarist, the Edge, told Rolling Stone a couple years after the record in question became an enormous hit for the Irish quartet. “We became interested in songs again. We put abstract ideas in a more focused form. It’s the first album where I really felt Bono was getting where he was aiming with the lyrics. Bono is more of a poet than a lyricist. With Joshua Tree, he managed, without sacrificing the depth of his words, to get what he wanted to say into a three- or four-minute song.”

Initially, though, the Edge and Bono disagreed about how to get to those really great songs. During U2’s various tours of the United States, the curiosity about Americana held by Bono, the band’s frontman, had grown into an overwhelming interest, and he wanted to explore the traditional sounds of R&B that were the foundation of rock ‘n’ roll. The Edge, however, was more invested in hewing to what he saw as more experimental, European musical forms, in part because his primary context was the warmed-over blues cheaply appropriated by various overpraised charlatans. While on the road for both The Unforgettable Fire and Amnesty International’s A Conspiracy of Hope tours, the band spent a lot of time on the bus listening to radio stations that specialized in music played by Black artists, especially gospel and classic blues. The Edge warmed to Bono’s thinking. Collectively, the band saw the approach as a way to buck against the overt studio sheen that was increasingly smothering modern rock and pop music.

With a few in-progress songs, U2 convened in the newly purchased house of their drummer, Larry Mullen Jr. to work through the material for a new album. The settled into a space with high ceilings and enormous windows that let in streams of natural light. Progress was slow, but Bono kept them locked into the thesis of commenting on America. As the songs came together, the foursome decided they liked the vibe of where they were playing to such a degree that they were best off recording there. Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois, co-producers of preceding studio album The Unforgettable Fire, were brought in again to work on the new one, the band’s fifth. Reflecting the motivating themes, the working title for the album was The Two Americas. It became The Joshua Tree after the band learned about the gnarled, durable desert growth during the photo shoot late in the recording process that provided the album’s cover art.

“You know, America’s the promised land to a lot of Irish people,” Bono noted not long after the release of The Joshua Tree. “I’m one in a long line of Irishmen, who made the trip to the U.S., and I feel a part of that. That’s why I embraced America early on, when a lot of European bands were throwing their noses up. And America, indeed, seems to have embraced us. Of course, my opinions have changed from utter stars in the eyes.”

Of course, The Joshua Tree was a triumph for the band in every way. It still stands as the most formidable realization of the concentrated friction that is U2 at their artistic peak: majestic and intimate, original and yet clearly derived from classic forms, emotional and just a little distant. As they stretched themselves on the album, U2 kept suggesting that they might benefit from bringing in some guests to back them up, but Eno and Lanois responded by insisting the band could handle whatever extra elements they wanted to introduce. There are fortifications here and there: the Armin Family provide strings on “One Tree Hill,” an agitated and anguished elegy for their fallen friend Greg Carroll, and the Arklow Silver Band play horns on “Red Hill Mining Town,” written about the U.K. miners’ strike in the mid-nineteen-eighties. Mostly, though, the album is performed by U2, making the vast landscapes of the songs all the more impression. There’s a pureness and honesty that makes the album hard to shake.

The Joshua Tree was also an enormous hit, raising U2 permanently into the upper stratosphere of rock bands. In the U.S., the album topped the Billboard album chart for nine straight weeks, and its first two singles, the aching “With or Without You” and the stirring “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” both also went as high at they go on the equivalent chart. The third single, the ever-building “Where the Streets Have No Name,” peaked outside of the Billboard Top 10 but absolutely felt as ever-present on the radio and MTV as its two predecessors. Although U2 had a strong following in the U.S., the almost immediate blockbuster status of The Joshua Tree was still a shocked. It was certified double platinum two months after its release and was over four million copies sold by the end of the year. By now, the count is over ten million in the U.S. and over twenty-five million worldwide.

Because U2 is so distinctive, the range found on The Joshua Tree is easy to overlook. Certainly, the affecting “In God’s Country” is as good a choice as any to present to a U2 novice to aurally demonstrate who they are, but the genuinely find very different gears to roll in across the album, including the piercingly delicate tale of heroin addiction “Running to Stand Still” and the inside-out blues of “Trip Through Your Wires.” Bono’s political anger at the U.S.’s geopolitical escapades, particularly in Central America — a major component of the self-education that dimmed those stars in his eyes — get drastically different expression in the burbling rock of “Bullet the Blue Sky” and the spare, harrowing “Mothers of the Disappeared.” As U2 hoped, The Joshua Tree goes on a purposeful quest and brings the listener along.

“I just think the album takes you somewhere,” bassist Adam Clayton told Rolling Stone. “It’s like a journey. You start in the desert, come swooping down in Central America. Running for your life. It takes me somewhere, and hopefully it does that for everyone else.”

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.