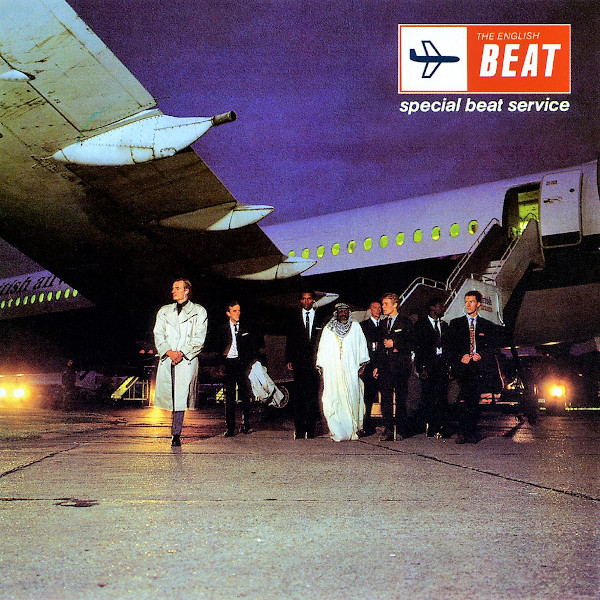

3. The English Beat, Special Beat Service (1982)

“We looked at ourselves and realized we had unconsciously overcompensated for the frenetic rhythms of the first album with the slower pacings of the second album,” Dave Wakeling, guitarist and vocalist with the English Beat, told a reporter as his band toured the U.S in early 1983. “On the third album, Special Beat Service, we combined the two and came up with our strongest album. We think now those transition days are over.”

If the transition days were indeed over, there was plenty of upending change leading up to that concluding point. After opening their recording career with three straight Top 10 hits in the U.K. and adding a fourth not long afterward, the band known simply as the Beat in their homeland saw a dip in radio programmer and consumer interest with the release of their sophomore album, Wha’ppen? Although the album itself hit exactly the same chart peak as its predecessor, the sterling debut I Just Can’t Stop It, its various singles performed tepidly.

The prevailing theory about the dip was that the group was a victim of the diminishing commercial popularity of ska music, once ascendent because of the faddish dominance of the so-called 2 tone movement, named after the label started by Jerry Dammers of the Specials. Keenly aware that the style was falling out of favor in the U.K., the English Beat looked to their new partners across the Atlantic for guidance. The band’s albums were released on their own label, Go-Feet Records, and were initially distributed internationally by Sire Records. Ahead of their third album, the English Beat instead signed a pact with I.R.S. Records, which had recently presided over a major hit with the Go-Go’s album Beauty and the Beat and was generally emerging as key tastemakers in college radio. Folks at the label encouraged the band to expand their palette, a strategy that in some ways brought them back to their original intentions anyway, or at least helped them transcend limiting perceptions about what they’d been up to all along.

“Radio programmers all over the world said, ‘Oh, that’s ska, innit?’ and put us in a little box,” Wakeling noted to Rolling Stone. “It annoyed us, because our idea was to blend punk and reggae. It ended up fast reggae, which, okay, did bear a passing resemblance to ska. But maybe we survived the ska revival because we never really were a ska band.”

To record Special Beat Service, the English Beat stuck with what they knew. As before, they set up shop in London’s Roundhouse Studios and worked with producer Bob Sargeant. There isn’t all that much punk present in what they produced, but the reggae is certainly still there. On “Spar wid Me” and “Pato and Roger Ago Talk,” the English Beat position themselves as proper conduits of those venerated island sounds. The latter track is especially notable as the debut of Pato Banton, a fellow resident of the English Beat’s hometown of Birmingham who would go on to be a significant reggae star. Banton was ushered onto the album by Ranking Roger, the English Beat’s charismatic toaster, after he won a talent contest where the more established performer served as a judge.

“I heard about the competition a half an hour before and joined the back of the line,” Banton recounted a few years later. “Straight away, five guys left the queue because they knew me. Then, I got stage and started dancing all around, and I kicked the mike cable, and they couldn’t hear me any more, so I just kept on dancing like crazy and went off stage. The crowds were roaring for more.”

The riotous energy Ranking Roger witnessed in Banton’s performance carries over to Special Beat Service, like a swarm taking over a whole region. The album opens with “I Confess,” which spins out like one of Joe Jackson’s jazzy, piano-driven romps, and “Sorry” opens with horn parts that hit like an avalanche moving at top speed followed by Saxa’s wailing saxophone serving as a strangely menacing echo of that cascade. “Jeanette” is built around jabbery rhymes, giving the impression of a track that’s moving faster than the speed of thought: “We met in a launderette and kissed beneath the air jet/ No sweat no threat/ Another one in the back of the net.” “Rotating Head” is tight and intense, and “She’s Going” adds a mambo verve to the already bustling proceedings.

If the English Beat were edging away from anything that might be deemed ska, they were clearly open to other on-trend sounds. “Sole Salvation” boasts a percolating post-punk rhythm that isn’t far off of what New Order was doing in that moment, when they were taking baby steps away from Joy Division. There’s a tingle of new wave to “Sugar and Stress” and “End of the Party” that puts the English Beat in the company of Modern English or Berlin. The mid-tempo album closer “Ackee 1-2-3” is like one of Elvis Costello’s genre experiments if he gave himself permission to use the first rhymes that came to mind for a change: “It would be a shame to take too much blame/ Look, we’re all the same/ It’s only a game.”

As the English Beat were trying to fill out the track list, they found themselves a little short of material. Wakeling suggested recording a song he’d written years earlier and had been trying unsuccessfully to introduce to the band’s repertoire. “Save It for Later” was derided by bass player David Steele as too mundane, a tired example of an older type of rock ‘n’ roll music. I.R.S. Records took Wakeling’s side, and their vote became decisive. With lyrics reportedly inspired by the discombobulation the comes with aging into young adulthood (“Two dozen other stupid reasons/ Why we should suffer for this/ Don’t bother trying to explain them/ Just hold my hand while I come to a decision on it”) and an acoustic guitar–based melody that recalls the best of the Jam (and genuinely earned everlasting envy from Pete Townshend), “Save It for Later” is downright glorious. Released as a single, it was a hit and wound up as the band’s most enduring song. Wakeling later estimated that “Save It for Later” accounted for around a third of the English Beat’s publishing royalties.

The execs at I.R.S. Records were so certain they had a winner with Special Beat Service that they convinced their major label distribution partner, A&M Records, to throw their weight behind promotions from the very beginning, a rarity for an outfit that preferred to wait and see if the indie records had legs before making an investment. They built a campaign around the slogan “Disturb the Rhythm, Break the Beat” and helped generated a towering stack of press, mostly built around interviews with Wakeling, seemingly the only member of the band who was amenable to sitting down with reporters. There were also a lot of concert dates across the U.S., both as a support act and a headliner. All that time on the road contributed to widening divisions in the band.

“Roger was sixteen when the group started, and Saxa was in his mid-fifties, and we all had different backgrounds and preferences, so we didn’t really have any peer group arguments because we kind of expected that everyone would think totally different from everyone, and whilst everyone was infused with all those various ideas into a melting pot, we got to the heart of the matter,” Wakeling later said. “But then a combination of people developing separate ambitions, and also some of really like working live and some people really didn’t like touring at all. They hated playing the same song over and over again and hated being on the road and eating crappy food and talking with drunk people for hours afterward, so that became a strain.”

Before long, the strain proved to be too much. Less than a year after the release of Special Beat Service, the English Beat formally disbanded and the members moved on to other projects. Most notably, Wakeling and Ranking Roger formed General Public, and Steele and guitarist Andy Cox continued working together, eventually teaming with a wildly gifted vocalist named Roland Gift to start the group Fine Young Cannibals. Big as those succeeding acts became, there were still some regrets among the band members that the English Beat ended when they did.

“People forget that when we were at our peak over in America we had the likes of R.E.M. and the Bangles opening for us,” Ranking Roger said many years later. “So as you can imagine we were over in America all of the time. It was simply too much for us to do. If we had been able to take six months or a year off and then got back together, then we could have done it. We would have made a proper fourth album and we would have been as big as UB40 were. I can even remember U2 opening for the Beat at Hammersmith Palais in 1982. I sometimes think, ‘Hang on, we could have been as big as U2.'”

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.