1. Go-Go’s, Beauty and the Beat (1981)

The rejection letter was breathtaking in its condescension. By the time the Go-Go’s were sending their demo around to labels, they had already proved themselves and developing a growing following within their local scene in Los Angeles. They had logged countless hours bashing about roughhouse club stages on their home turf, where they had the challenge of rising above the angry clamor of messy punk bands, and they had further proven their mettle as a support act for the likes of Madness and the Specials, spending months touring the U.K., often in front of unfriendly crowds that were impatient for the rowdy ska act they’d come to see. The Go-Go’s even had a successful single out already. Released on cooler-than-cool U.K. label Stiff Records, “We Got the Beat” had a pleasantly punky energy and garage-rock roughness and yet was grounded enough in buoyant pop that it managed to edge onto the Billboard dance music chart. Despite all these promising developments, label after label expressed no interest in signing the Go-Go’s. “Best of luck with your enterprising girl band!” the letter stated.

No one tried to hide their chauvinism. Gender was the explicitly stated issue that record executives had with the Go-Go’s when assessing their commercial viability. The band was comprised of five women: lead singer Belinda Carlisle, lead guitarist Charlotte Caffey, rhythm guitarist Jane Wiedlin, bassist Kathy Valentine, and drummer Gina Schock. That was it, the only concern anyone had about the act. It’s not like the band was playing militantly feminist music as some sort of precursor to the riot grrrl movement. They were just a rock band that started and progressed like any other collection of people that decided to make music together. Their origin story, when dates to 1978, is exceedingly familiar.

“The underground music scene in L.A. consisted of only about one hundred fifty people at the time, and all our friends were in bands,” Carlisle once explained to The Toronto Star. “So we decided that if they could get away with being terrible and not playing well, so could we. So we just started playing and learning as we went along, but you could get away with not having any great musical knowledge of anything back then.”

By their telling, the all-female lineup of the band was entirely coincidental. Even when roster changes occurred — such as original drummer Elissa Bello leaving and being replaced by Schock or founding bassist Margot Olavarria getting ousted in favor of Valentine, a guitarist who learned a new instrument just to join the band — the absence of Y chromosomes among the membership was a matter of happenstance rather than design. The Go-Go’s weren’t trying to make a statement. They just wanted to play.

After it felt like everyone else had passed, the Go-Go’s got an offer from I.R.S. Records, a relatively new label headed up by Miles Copeland. Copeland was the eldest sibling of Stewart Copeland, the drummer with the Police, and he managed his kid brother’s band. Copeland parlayed his organizational and promotional contributions to the Police’s success into getting the band’s label, A&M Records, to help bankroll and distribute this new indie label venture. In the early going, I.R.S. Records was a home for thrilling oddballs and outcasts. They released albums by the Fall, the Cramps, Rootboy Slim & the Sex Change Band, and, perhaps most significantly, Buzzcocks. That last act was a major touchstone for the Go-Go’s. Granted, I.R.S. Records was the only label to pass a pen and a contract over to the Go-Go’s, but surely being labelmates with the only artist that every last member of the quintet cited as an aspirational influence held some appeal.

Copeland was a true believer in the potential of his newly signed act, and the Go-Go’s were immediately shipped off to New York to record their debut album. To produce the record, I.R.S. Records enlisted Richard Gottehrer, a crack pop songwriter in the nineteen-sixties who’d gone on to have an enviable career behind the board. He was particularly good at guiding acts to memorable debut albums, producing or co-producing the initial outings for Richard Hell and the Voidoids, Blondie, and, one year after working with the Go-Go’s, Marshall Crenshaw. Like Copeland and other early adherents of the band, Gottehrer could see and hear that the Go-Go’s were special.

“They were the absolute of what a great band is,” Richard Gottehrer later said. “A great band doesn’t have to have virtuoso musicians, they just need to make an interesting sound when they play together that makes you wanna learn more about them. Blondie weren’t virtuoso musicians but they were a great band, and so were the Go-Go’s. So, I agreed to do the record.”

Their collective spine steeled by regularly playing concerts to crowds that were skeptical at best and downright hostile at worst, the Go-Go’s went into the recording sessions with a certain amount of self-assurance. They were still raw and hungry, to be sure, and they were excited about finally getting the chance at real rock stardom they’d been striving for (which also manifested in reckless, debauched behavior that would eventually be a significant factor in the band’s undoing). When it came to their songbook, the Go-Go’s felt secure.

“Subsequent Go-Go’s albums had the added stress of writing new material but we went into Beauty and the Beat having already figured out which songs worked,” Caffey noted. “We were developing who we were as a band and it got reflected in this timeless piece of work.”

Although the band had figured out which songs worked, Gottehrer had some clear ideas about how those same songs could work better. Much as the Go-Go’s still thought of themselves as kindred creatives spirits with all those L.A. punk bands they’d shared bills with, Gottehrer heard the pure pop instincts within their songs. In part because there was already a recorded version of it out in the world, “We Got the Beat” is the clearest representation of how his approach reshaped the tunes the band brought into the studio.

“When it came time to record ‘We Got the Beat,’ they were reluctant because in their eyes it had already been a hit as an import single,” Gotterhrer later explained. “It sold well by punk standards — around fifty thousand copies or something — but they didn’t realize this song could be an actual hit, so I made them do it again. I slowed it down, made it more precise, and doubled the drum parts because if you’ve got a good beat, the more the better. What you hear is the Go-Go’s leaning into the process of turning good songs that some people liked into something more precise that enabled their sound to spread wider.”

Whether the Go-Go’s were actually eager participants in transforming those good songs is a matter of debate. In most recollections of the time, individual band members went along reluctantly with Gotterhrer’s suggestions or were crestfallen when they heard the finished product. What had once been bruising and brusque was now gleaming and sweet, recalling classic girl groups of the nineteen-sixties more often than banging rockers of the same era. There are times when the vestiges of a louder, rougher version of the Go-Go’s linger on a track like a ghostly apparition of times past. The tangy harmonies of “Tonite” mingle with a steady, pogoing beat and lyrics that smack of defiance (“There’s nothing/ There’s no one/ To stand in our way”), and “This Town” has some gnarly guitar parts to go with its soaring chorus and practically perfect pop trappings.

No matter how perturbed the Go-Go’s might have been at first, the shift in tempo and other basic fundamentals of how the songs were played just made sense. Gotterhrer felt slowing the songs down let them breathe and exposed the impeccable, if largely instinctual, craft at the core of them. He believed in the quality of the album enough that he put up several thousand dollars of his own money to finish it after the relatively paltry thirty-five thousand dollar budget afforded by I.R.S. Records ran out. The collective abilities of the Go-Go’s were brightly highlighted on the album, and it came through more resoundingly than it likely would have without the recalibration.

“The thing is, a well-crafted song is a well-crafted song,” Valentine said later. “You could slow down a Buzzcocks song, or you could take ‘God Save the Queen’ — the elements of a good song are there, whether it’s played fast or snarled or pounding 16th notes. So the Go-Go’s, the bones of our songs were well-crafted, hooky, with smart lyrics.”

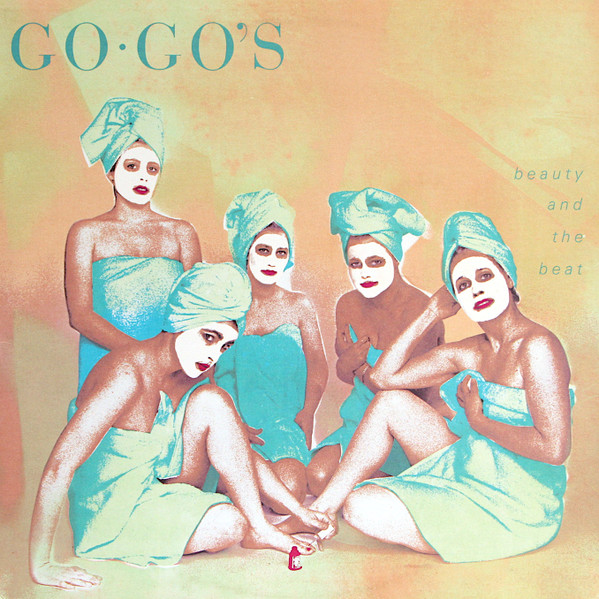

The album was given the title Beauty and the Beat, attention-getting wordplay that is generally attributed to Carlisle. The striking album cover was also Carlisle’s invention, playing on the title with a visual of the band appearing to get beauty treatments, wrapped in towels and under heavy applications of facial cream. As a bonus, the cover image freed them from having to make decisions about what clothes to wear. They weren’t there to make a fashion statement anyway. The album cover was deviously deglamorizing.

For the first single, I.R.S. Records opted for “Our Lips Are Sealed,” a composition by Wiedlin that started from lyrics sent to her by Terry Hall, of the Specials and Fun Boy Three. Wiedlin and Hall raced through a doomed affair when the Go-Go’s toured with the Specials, and the lyrics alluded to keeping silent in the face of external gossip: “Pay no mind to what they say/ It doesn’t matter anyway/ Hey, hey, hey/ Our lips are sealed.” Fortuitously, the Police had returned from a video shoot and proudly declared they came in under budget. Copeland took that spare six thousand dollars and diverted it to the Go-Go’s. The band spent a day driving around Beverly Hills in a old Buick convertible and capped off the sweltering afternoon by splashing around in an outdoor fountain. The resulting music video became a mainstay on the new cable network MTV, which drove the song into the Billboard Top 20. The video, like the song itself, comes across as vibrant and joyous. Founding MTV VJ Mark Goodman later observed that the music video was a success because the Go-Go’s came across as people “you wanted to hang with.”

“We’re a positive band,” Caffey said at the time. “Just the exciting fact that after three years we’re finally getting to do this shows up in our music. Right from the start, the band has always been based upon having fun. I know that sounds corny, but it’s really true.”

Boasting a hit single, Beauty and the Beat started moving a lot of units, and music fans who added it to their collections found a set of sterling songs. There is definitely a sense of throwback across the album, whether the classic sixties pop jangle of “How Much More” or the punchy Bo Diddley beat on “You Can’t Walk in Your Sleep (If You Can’t Sleep),” which benefits from especially sweet Carlisle vocals making the fairly dire lyrics feel playful (“Which way will things go tonight?/ Toss and turn or sleep tight?/ You can’t win, you wonder why/ That sleep is one thing you can’t buy”). “Lust to Love” is a classic bad romance pop saga (“Love me and I’ll leave you/ I told you at the start/ I had no idea that you/ Would tear my world apart”), the bittersweet heartbreak that was the speciality of a legion of girl groups given a modern polish that almost sounds like the lo-cal version of Jim Steinman’s famed excess.

The album isn’t strictly a retro play, though. Without sounding particularly beholden to new wave, many of the cuts bristle with the energy of that cultural moment, when establish pop forms could be given an expectation-upending makeover. “Automatic” is a slyly strange, skulking ballad, “Can’t Stop the World” is bright, headlong pop, and “Skidmarks on My Heart” has a jolting brashness that anticipates the rule-breaking female-dominated bands of the next era (“I buy you cologne/ You want axle grease/ You say get a mechanic/ I say get a shrink”). The downbeat, cascading guitar opening of “Fading Fast” genuinely sounds like something Sleater-Kinney might have included on The Woods. Thrillingly, the Go-Go’s are hard to pin down.

“Everybody was influenced differently growing up, and I think putting all that together, we come up with the Go-Go’s sound,” Schock told a reporter. “I listen to us, and I can’t say what we sound like or what we are. I guess you could just say the Go-Go’s are for everyone.”

As the album continued its roll-out, Schock’s assertion of universal appeal proved to be remarkably accurate. Taking advantage of their label boss’s connections, the Go-Go’s secured a high-profile spot opening for the Police as they toured in support of their hit album Ghost in the Machine. While on the road, “We Got the Beat” was released as the second single from We Got the Beat, and it roared up the charts. The song spent three weeks at #2, blocked from the top by Joan Jett & the Blackhearts’ seven-week stranglehold on that position with “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll.” Simultaneously, Beauty and the Beat did reach the pinnacle of its Billboard chart, staying there for six weeks.

Beauty and Beat was the first album by a rock band comprised entirely of women to hit #1. More than that, it is generally considered the first album by an all-woman band to even crack the Top 100 of the Billboard album chart. The two main predecessors of the Go-Go’s didn’t even come close: Fanny made it no higher than #135 (with the 1972 album Fanny Hill), and the Runaways’ chart peak was #172 (with their sophomore album, Queens of Noise).

Overjoyed by the success of Beauty and the Beat, the first real hit in their nascent catalog, I.R.S. Records execs wanted to ride the album for as long as they could. Michael Plen, the head of promotion who’d gone town to town to sing the praises of the album, was among those pleading with the band to keep chugging away with the their debut release. Plen was trying to heed advice he received from Charlie Minor, who held his same position at I.R.S. Records’ more seasoned major label partner, A&M Records, but the Go-Go’s weren’t having it.

“They’d become cocky, and their attitude was, ‘We’re tired of this material. We want to make a new record,'” Plen said many years later. “Wikipedia says there was a third single from the album, but I can tell you, there wasn’t, not in the proper sense. They put the brakes on an album that could have easily released another hit. We had arguments about it, and I remember Charlie Minor said, ‘You don’t ever stop a record that’s selling.'”

When Beauty and the Beat was still ascendent, the Go-Go’s charged back into the studio to make their sophomore album, Vacation. The second album hit record stores almost exactly one year after the first. When Vacation debuted on the Billboard album chart, Beauty and the Beat was still in the Top 100. The worries of the record company were sound. Beauty and the Beat logged double-platinum sales, but Vacation sold about a quarter of that, stalling out as a gold record. The trend of diminishing returns continued with the band’s third album, Talk Show, and the Go-Go’s disbanded not long after.

“We always say we’ll keep doing it as long as it’s fun, we enjoy each other, and the music is good,” Wiedlin said as the Go-Go’s were still riding the massive wave of Beauty and the Beat. “But I don’t think anyone’s really afraid of moving on. I think there’s a lot of bands that stop being popular that are afraid to let go of it, like they don’t have any identity outside the band. There are other things that any of us can do. We have other talents. It’s great what’s happening to us, but it isn’t forever.”

Reunions followed the breakup, but so did lawsuits and other fraught, fragile circumstances as the bandmates kept circling back to one another every time it became clear that there was only so much available to them as individuals. Cultural nostalgia for their genuinely glorious glory days remained the most lucrative chit they held. Through it all, the Go-Go’s were often denied the respect they so clearly deserved. Too often, the music industry continued to relegate them to the status of cute novelty act. It’s only been in recent years that they’ve gotten their due, marked by an adoring feature documentary and belated induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The enterprising girl band didn’t need luck; they had fierce, uncommon talent. And, in the end, talent wins out.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.