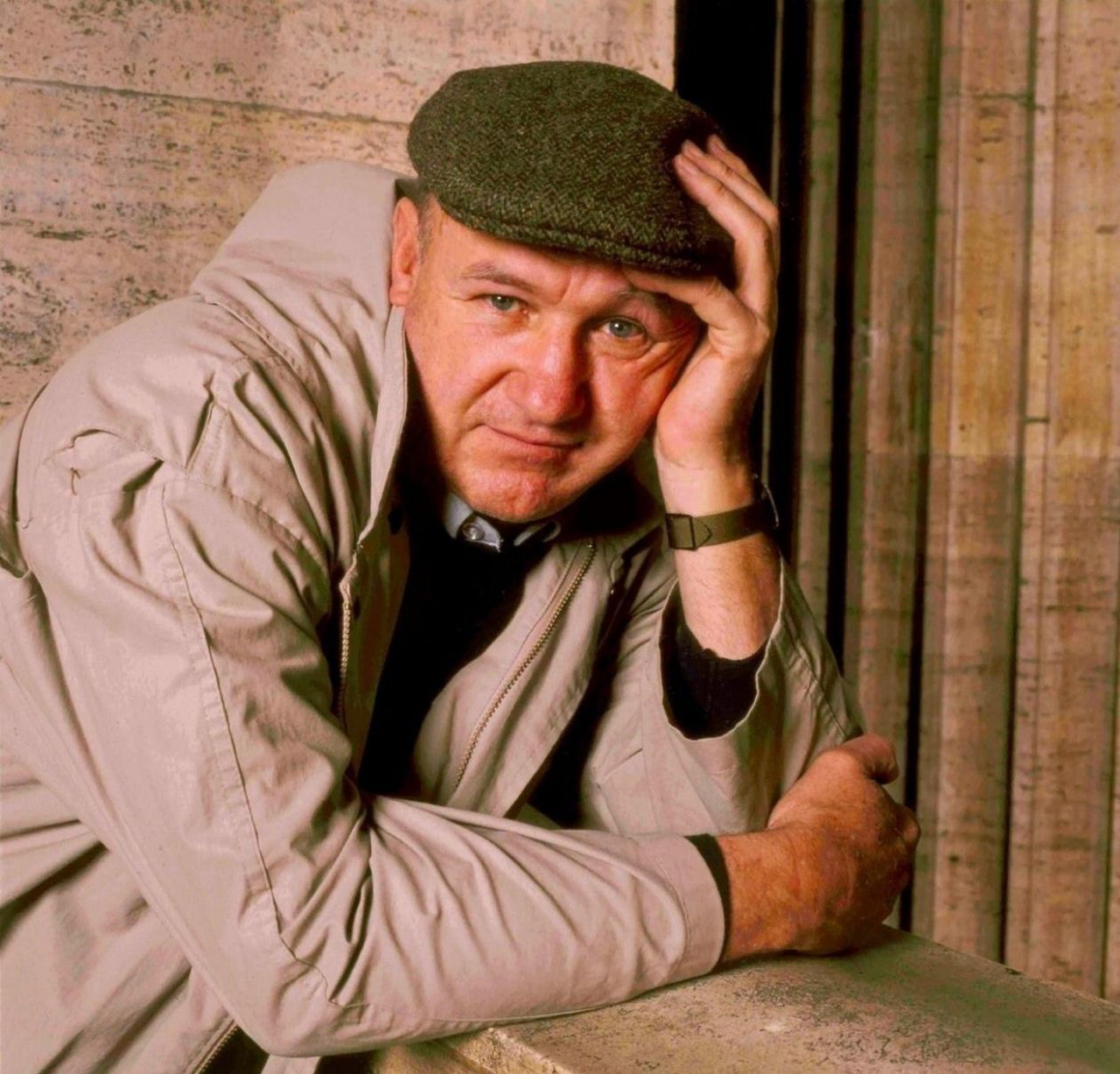

About fifteen years ago, Gene Hackman came to the city where I lived. He wasn’t there to shoot a movie. That portion of his life was solidly behind him at that point; following a few temporary retreats from the grind of being a working actor, Hackman had finally made retirement from showbiz stick. Instead, he was there to promote Escape from Andersonville, a historical fiction novel he wrote with his friend Daniel Lenihan, one of several that bore both their names on the spine. Hackman was charming as he spoke to the crowd assembled in the downtown independent bookstore, clearly aware that it was his movie-built celebrity that lured the crowd there and consistently gracious in trying to expand the spotlight to include his less famous co-author.

I was grateful that my fellow attendees correctly read the room and confined their Q&A contributions the the topic of writing. The only time the conversation strayed to Hackman’s time in Hollywood was when someone asked if there was character in the story that could coax him back into acting if the book were adapted for the screen. Hackman chuckled and said there wasn’t. He then reassured everyone there were plenty of opportunities to still watch him act. Just go rent one of his old movies, and he genially listed a couple off. I found it telling that the first title he mentioned was Hoosiers. That feels like the kind of performance that Hackman himself would appreciate: a little irascible but imbued with decency and delivered with a thoughtful care that looked like ease, probably deceptively so.

Hackman won two Oscars in his career, both for deeply worthy performances. He probably deserved to win more. At the very least, I’d say he gave the best performances of the year — not just for whatever category he would have been placed in but of all film actors in all roles — in 1988, in Mississippi Burning, and in 2002, in The Royal Tenenbaums. To this day, whenever I point out that Hackman wasn’t even nominated for an Academy Award for his amazing performance in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, I have to go and double-check. I just did. That’s how unbelievable it is to me. If pressed to select the best film performance of all time, Hackman’s turn as Harry Caul is the one I would name. Given a character who’s insular by nature, Hackman burrows so deeply into him that I almost have a hard time recognizing it as acting. It’s more like embodiment.

It’s probably not quite right to say that Hackman never gave a bad performance, but I’d have a hard time naming one. Even in subpar material, and there was plenty of that across Hackman’s long career, he brought a strident authenticity to his work. Even when he was clearly screwing around a little bit — as Lex Luthor in the Superman films, as the villainous gunslinger mayor in Sam Raimi’s underrated Western The Quick and the Dead, playing the popcorn movie version of Harry Caul in Enemy of the State — Hackman couldn’t help but make the character grounded and real. When the film’s artistry matched Hackman’s own, he was virtually unmatched. There’s a reason his Best Supporting Actor Oscar win for Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven was in little doubt from the moment the Western first flickered up on a screen. Part of his brilliance was the way he could play individual moments just a shade off of what was expected, putting a little English on the ball, as still make them perfectly natural. This quality was especially impressive with dialogue that surely looked very plain on the page; think of him as Senator Keeley in The Birdcage, discussing the family drive to Florida with numbing aimless detail that is a more brutal a takedown of the vacuousness of political rhetoric than can be found in the most focused, complex satires.

When I saw Hackman at the bookstore all those years ago, he acknowledged that he still liked acting. It was the business that he couldn’t abide any longer. It is hard to imagine what the current filmmaking ecosystem could have offered an actor like him. Superman notwithstanding, I don’t envision him getting much purchase or satisfaction in a time when costly tentpoles or inventively frugal indies are the only options. Hackman plied his trade in movies that strove for meaning rather than spectacle, that scratched around at humanity with an eager sense of discovery. Luckily, those movies were available to him for a long time. And those of who look to that big screen for inspiration and to help make meaning of a mixed-up world, we are the beneficiaries.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.