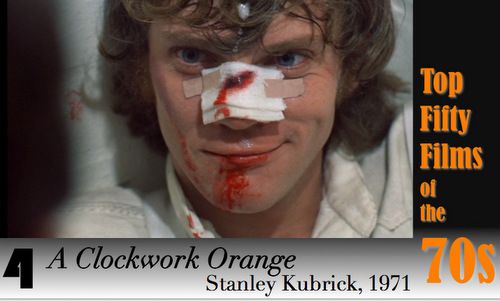

#4 — A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is widely considered a classic. I can’t think of another film in the same exalted status that is as brilliantly, exuberantly, comically savage. In adapted Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novella of the same name, Kubrick tore free the ferocious id of humanity and laid it bare, ultimately questioning whether the true problem was the roiling internal rage and impulsive hedonism of people or the cloying attempts of society to contain those instincts. Untamed passion may lead to random acts of violence and terror against innocent people, but isn’t that also the pathway to the thundering masterworks of Beethoven? Safer streets are nice, but what is free will is scrubbed away along with the crime? Acknowledging that humans are animals may be the vital first step towards accepting the astounding zoo that is the world. Sheets of chilling rain add darkness to existence, but there’s always still a chance to sing in it.

Set in London at some indeterminate point in the future, the film features Malcolm McDowell in a performance of exuberant malevolence as Alex DeLarge, the ostensible leader of a band of codpiece-adorned youths known as “droogs” who while away the hours creating random havoc. This is usually directed outwards, but occasionally includes a well-placed swing of a stick against the knee of one of their own. When the mayhem against others perpetrated by Alex escalates to murder, he’s institutionalized, eventually leading to the iconic image of his eyes pried open, kept moist by administered eye drops, as he’s forced to watch imagery specifically designed to reprogram him into crippling revulsion at the thought of violence. It’s an existential eye-for-an-eye, rendering him psychologically lifeless for the crime of taking a life. The film revels in its malicious impishness, absolutely refusing to allow for nobility or intellectual honesty in anyone’s actions.

Kubrick, always a maestro of the artful visual crescendo, reaches vertiginous new heights throughout A Clockwork Orange. It is sharply drawn and grandly enraptured with the static dynamics of physical spaces. The trademark chilliness of the director is in place, and it has arguably never had a more fitting outlet. The sterility of certain moments, images, techniques is stuck in a friction-filled duet with the messy, bloody pummeling of the story. Kubrick’s clinical eye exposes the spiritual agony at the heart of the whole endeavor in a way that a more empathetic director never could. That its further presented as the bleakest of satire, and is often shockingly funny, is one of Kubrick’s greatest, sickest jokes. The film shudders like a menacing chortle of virulent glee.

I’ve little doubt that A Clockwork Orange represents the clearest distillation of the director’s view of the world. From at least 1957’s grim war drama Paths of Glory onward, Kubrick kept reiterating a thesis of man’s willing destruction of self, a subsuming of the human spirit to forces destined, even designed, to tear it to ugly shreds. If A Clockwork Orange is his final full-fledged, unqualified masterwork, then it’s perhaps because he created a closing argument of sorts, a statement of assured belief so strong that it could hardly be refuted. All of society’s ills are met with the worst, most reactionary solutions, a thrilled welcoming of a wrecking ball in the guise of purifying salvation. That Kubrick could convincingly depict the tragic weight of all that misguided foolishness and still laugh–harshly and with pity, perhaps, but clearly laugh–is some of the clearest evidence he was operating on a totally different level of cinematic brilliance.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.