672. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, The Pacific Age (1986)

“There are a lot of people out there who may now consider OMD to just be ‘If You Leave,'” bassist Andy McCluskey told Billboard upon the release of The Pacific Age, the seventh studio album by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. “Obviously, it helped us get exposure in America, but we want people to know we are capable of a lot more than just that particular type of song.”

After years of significant success at home in the U.K. and only the slightest headway on the U.S. charts (they’d landed in the Top 40 with the 1985 single “Crush”), OMD were gifted prime placement on the 1986 teen romantic comedy Pretty in Pink, written and produced by John Hughes. Anyone expecting the title song, the Psychedelic Furs’ freshly recorded, spruced up take on their own 1981 single, to become the soundtrack’s breakout hit hadn’t been paying close enough attention. As Simple Minds proved, it was the yearning, preemptively nostalgic ballads that ruled the day. All those proms need theme songs, you know. According to lore, OMD wrote “If You Leave” in less than twenty-four hours, responding to an emergency call from the filmmakers, declaring poor test screenings mandate the shooting of a new ending for Pretty in Pink, and the band’s original submission for a closing song no longer made sense. Despite the haste in which “If You Leave” was written (or perhaps, in part, because of it), the song become a smash.

Seven months after the Pretty in Pink soundtrack hit record stores, OMD released The Pacific Age. The timing was right to exploit the band’s newfound prominence. The music on the record, however, pushed back against that opportunity. McCluskey’s insistence that the band had versatility beyond the swooning power ballad that made their fame was evidenced by an album that strayed from not only that sound, but the sound of most prior OMD records.

McCluskey and his chief partner in the band, keyboardist Paul Humphreys, deliberately brought a different approach to the development of their songs for The Pacific Age, supposedly in an attempt to capture the energy of their live shows. The contradictory result of the expansive creative process is an album full of songs deadened by a lack of focus. “Stay (The Black Rose and the Universal Reel)” is like a tepid version of Tonight-era David Bowie (which isn’t that great to begin with), and “The Dead Girls” is OMD’s usual sound thickened with molasses. At times, the material is widely misguided. “Southern” is a weird meshing of cheerily empty disco with the passionate Civil Rights rhetoric of Martin Luther King, Jr. “Goddess of Love,” the original Pretty in Pink soundtrack contribution, is reclaimed for The Pacific Age, proving the last-minute change was deeply fortuitous. It’s difficult to image this clomping, inane cut (“She can’t afford dreams/ And her clothes are old/ She can’t afford hope/ Wouldn’t be so bold/ But she’s holding his heart/ And she won’t let go again”) becoming a similar commercial breakthrough.

There are a few glints of inspiration among the tangle. The easygoing romantic pop of lead single “(Forever) Live and Die,” which became OMD’s third Top 40 hit in the U.S., forecasts the glistening perfection of Ian Broudie’s the Lightning Seeds. And it’s a testament to the quality of “We Love You” that a straight line can be drawn from it to the retro dance floor gems released by Cut Copy and similar acts a couple decades later. These are exceptions, though. Most of The Pacific Age is muddled and sluggish. And the band seemed to feel it, too. Shortly after the tour to support the album, OMD basically fell apart. Only McCluskey remained, essentially borrowing the established band name as a commercially helpful costume for his solo work over the course of the next several years.

671. John Cougar Mellencamp, Scarecrow (1985)

One album after first asserting his own identity enough to put his real last name on the cover, John Mellencamp made it completely plain who he was and what he believed in with Scarecrow. His eighth studio album overall, it was the first Mellencamp recorded in the studio he built in Belmont, Indiana. More important, Scarecrow found Mellencamp pushing himself beyond the simple, tied-tested rock ‘n’ roll songwriting topics of love, heartbreak, and the relentless pursuit of good times. The album leads off with “Rain on the Scarecrow,” a pained, angry lament for family farms set to a fierce beat provided by the one true ringer in Mellencamp’s backing band, drummer Kenny Aronoff. The performer who was once crammed into the cheap rock persona Johnny Cougar now had something important to say.

The politically enlivened songs are spread all across Scarecrow. To different degrees, the percolating “The Face of the Nation,” boisterous “Justice and Independence ’85,” and name-dropping “You’ve Got to Stand for Somethin'” (“I’ve seen the Rolling Stones/ Forgot about Johnny Rotten/ Saw the Who back in ’69”) all weigh in on the fraying of the social fabric, offering commentary on the need to fight back against corrupting forces holding back less-powerful citizens from achieving even a modest version of the American Dream. Even Mellencamp’s more familiar songs are tinged with a melancholy outlook that suggests a populace adrift. On the surface, “Lonely Ol’ Night” is standard lovelorn rock ‘n’ roll, but, in the context of the political outlook of the album, the lyrics “And it’s a sad sad sad sad feeling/ When you’re living on those in betweens” cut a little differently.

“Rain on the Scarecrow” might lend the album its title, but “Small Town” is the true thesis statement. Romantic and appreciative of the charms of living within a sparsely populated community, Mellencamp is also honest enough to acknowledge the shortcomings (“My job is so small town/ Provides little opportunity”). He comes down firmly in favor of sticking with the small town, but an awareness of the potential for improvement provides impetus to call out for more support, more respect, more understanding. Keeping his eyes wide open gives Mellencamp reason to sing.

670. Daryl Hall and John Oates, Private Eyes (1981)

Daryl Hall and John Oates were determined they weren’t going to let opportunity pass them by again. The duo enjoyed a flare of major success in the middle of the nineteen-seventies, when the hit “Sara Smile” set off a run of five straight Top 40 hits, including the chart-topper “Rich Girl.” Then the broader mainstream enthusiasm for their music dissipated. Hall and Oates remained prolific, releasing an album per year through the late seventies, but the singles from Beauty on a Back Street, Along the Red Ledge, and X-Static made few to no ripples. The 1980 album Voices seemed to following that course when a cover of the Righteous Brothers’ classic “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling” made significant headway on the charts. The next single, “Kiss on My List,” spent three weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100, and, just like that, Hall and Oates were back to being a force in pop music.

The duo were in the studio working when “Kiss on My List” broke, and they quickly made adjustments designed to help them build on their revived profile. They tightened up their songwriting methodology and took greater care in the recording process, logging over one hundred separate sessions at Electric Lady Studios, in New York City. The resulting album, Private Eyes, cemented Hall and Oates as dependable hitmakers. The record’s first two singles — the title cut and “I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)” — both went all the way to #1. For the rest of the decade, Hall and Oates were mainstays in the Billboard Top 40.

While it’s genuinely difficult to deny the appeal of the duo’s hits, digging deeper into a Hall and Oates album unearths no long-lost treasures. On Private Eyes, “Looking for a Good Sign” is like a discard from an especially toothless version of J. Geils Band, and “Your Imagination” is a big, cumbersome glob of pop-rock. The slight power pop vibe on “Tell Me What You Want” invites speculation on how the act could have pursued slightly more daring music, but it’s an aberration. The chintzy synths and numbing redundancy of “Did It in a Minute” is the more accurate barometer reading on their artistic outlook. Private Eyes is a reminder of why greatest hits collections exist.

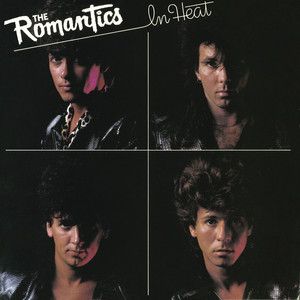

669. The Romantics, In Heat (1983)

The Romantics were nearly done with their fourth album, but they needed one more song. As they were brainstorming, producer Peter Solley suggested bassist Mike Skill revive a riff he’d been noodling with earlier. His bandmates joined in, jamming and exploring until they’d built a solid musical foundation. The song kept developing, and the Romantics completed the album In Heat by laying down a new composition entitled “Talking in Your Sleep.” Released as a single, the cut became a major hit, making it all the way up to #3 on the Billboard chart.

If nothing else on In Heat is as strong as the hit, the material is all reasonably solid. The Romantics consistently deliver retro rock dressed up with a far more modern production sensibility, the songs built on slick hooks and forgettable lyrics, mostly finishing off with an amusing repetitiveness that makes it seem as if they considered every track a candidate for the runout groove. The only flirtations with complexity come in the odd, likely inadvertent passages where the band sometimes seems to be engaged in a dialogue of standard-issue rock sentiments, as when “Do Me Anyway You Wanna” is answered within a couple turntable rotations by “Got Me Where You Want Me.”

The norm on In Heat is the straightforward and agreeably dopey “Rock You Up” (“You want to do a little dancing/ Well music never let you down/ But if you’re ready for romancing/ Honey, better hang around”). Even the occasional flutters of stylistic variance — the sweet power pop of “One in a Million,” the pogoing energy on “I’m Hip” — don’t stray all that far from the model. Emphasizing the backward glance inherent to their approach, the Romantics close the album with a limp cover of “Shake a Tail Feather.”

Having a hit single to their name afforded the Romantics many things, the most fruitful of which was a cause for skepticism when the bankbooks of the band members didn’t seem to reflect their success. According to Skill, he and his cohorts analyzed their finances and determined the band’s management was skimming from them. The business relationship was broken off, and the Romantics took their former managers to court, eventually winning back ownership of their songs, one of the most lucrative commodities a music act can hold.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.