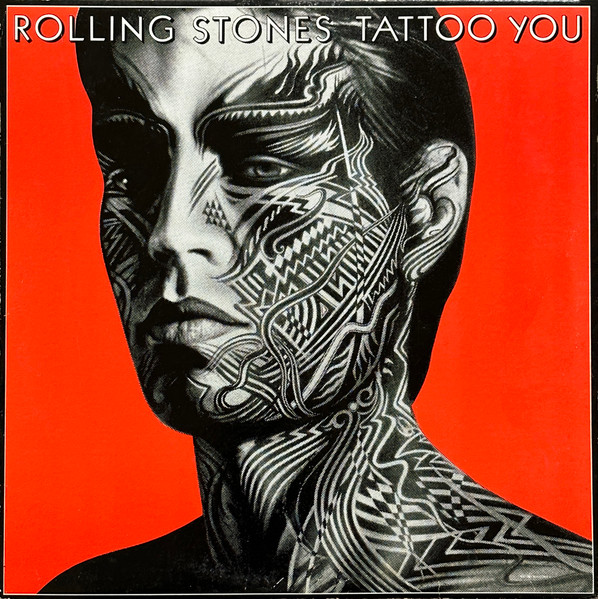

7. Rolling Stones, Tattoo You (1981)

The Rolling Stones were in a precarious place. Commercially, they were as strong as ever. The 1978 album Some Girls was their biggest-selling album to that point in the U.S., and its follow-up, Emotional Rescue, was also a sizable success, becoming the band’s first studio outing to top the U.K. chart since the 1973 release Goats Head Soup. Behind the scenes, though, relationships between bandmates were dire. Accurate as it probably is to say that there was animosity all around, gauging the spiritual health of the Rolling Stones always begins with putting a diagnostic eye on the relationship between the Glimmer Twins: lead singer Mick Jagger and lead guitarist Keith Richards. By all accounts, their interactions were going poorly.

“The phrase that rings in my ears all these years later is “Oh, shut up, Keith,'” Richards wrote of Jagger’s treatment of him in his memoir, Life, published some three decades after the time in question. “He used it a lot, many times, in meetings, anywhere. Even before I’d conveyed the idea, it was ‘Oh, shut up, Keith. Don’t be stupid.’ He didn’t even know he was doing it — it was so fucking rude. I’ve known him so long he can get away with murder like that. At the same time, you think about it; it hurts.”

For his part, Jagger tended to blow off inquiries into tensions within the band. By the early nineteen-eighties, it was basically an open secret that Jagger and Richards were feuding, so music journalists would ask about it. Jagger, ever the salesman, might acknowledge squabbles, but he also projected a certain steadiness, insisting it was all business as usual.

“Well, it’s always a problem, being in a band,” he told a reporter who specifically asked about problems within the ranks of the Rolling Stones. “It sometimes is annoying because in a band like this one, you do sort of have to not tread on peoples’ toes too much. It’s very hard governing by committee.”

One of the ways Jagger had already stomped on his cohorts’ toes was by refusing to go out on tour in support of Emotional Rescue. Many months later, Richards was still itching to get the band on stage. In March 1981, Jagger met with Richards and the two hashed out an agreement to launch a tour in the fall of that year. Most of the band members figured it just might be a farewell tour; they proceeded nonetheless. The prevailing model in that era was that an act needed a new album out in the marketplace to justify hitting that road. That was true even for a mighty band such as the Rolling Stones.

As tour dates were committed, it became clear that the fraught reconciliation between Jagger and Richards only went so far. Under the best of circumstances, there was a tight timeframe available to them for writing and recording ahead of loading up the tour buses, and it was far from the best of circumstances. Getting together to work on new songs simply wasn’t going to happen.

When presented with the problem of how to generate a whole new Rolling Stones studio album while Jagger and Richards could barely look at one another, Chris Kimsey, who’d been employed as the Rolling Stones’ studio engineer with some regularity, came up with a solution. Kimsey knew firsthand that the band had a lot of partially finished tracks stacked up in the vault. There might be enough among those discards to at least provide a reasonable head start in crafting a full LP.

“I spent three months going through like the last four, five albums finding stuff that had been either forgotten about or, at the time, rejected,” Kimsey said. “And then I presented it to the band and I said, ‘Hey, look, guys, you’ve got all this great stuff sitting in the can and it’s great material, do something with it.'”

Many of the shards came from the sessions for Emotional Rescue, but Kimsey’s salvage operation stretched back nearly a decade, all the way to Goats Head Soup. Little of the promising material Kimsey found was in a state that could be considered finished, so there was still work to do. According to Jagger, he brought the tracks to completion more or less on his own, chugging away until he had enough for a finished album. The album was dubbed Tattoo You.

“A lot of them didn’t have anything, which is why they weren’t used at the time — because they weren’t complete,” Jagger later told Rolling Stone. “They were just bits, or they were from early takes. And then I put them all together in an incredibly cheap fashion. I recorded in this place in Paris in the middle of the winter. And then I recorded some of it in a broom cupboard, literally, where we did the vocals. The rest of the band were hardly involved. And then I took it to Bob Clearmountain, who did this great job of mixing so that it doesn’t sound like it’s from different periods.”

To help disguise the album’s origins, there were no credits included on the jacket. Jagger initiated the act of subterfuge, knowing that properly citing bygone players such as Mick Taylor or Wayne Kramer would have been a dead giveaway. Any worries that fans might sniff out the patchwork creation and reject the album were eradicated when lead single “Start Me Up” became a smash. It almost immediately claimed a prominent place among the most iconic Rolling Stones cuts, largely thanks to the quintessential Richards guitar riff that drives it, a riff that had been plucked out of the middle of an earlier reggae-tinged pass at the song.

Appropriately, “Start Me Up” is the opening track on the album. The cut is the guide for the whole first side of Tattoo You. As if to reassure the longtime fans who were a lukewarm on the band’s dalliances with disco on their two preceding albums, Tattoo You leads with with six straight songs that are pure Stonesy rock ‘n’ roll. After the opener comes “Hang Fire,” a groovy rave up, and “Slave,” which delivers redundant grind and prowl that’s interrupted by some spoken word yammering by Jagger (“24 hours a day/ Hey, why don’t you go down to the supermarket/ Get something to eat, steal something off the shelves/ Pass by the liquor store, be back about a quarter to 12?”). The latter track features arresting saxophone parts by Sonny Rollins, a jazz legend who was recruited to help flesh out some of the songs. Although it was drummer Charlie Watts, a longtime devotee of jazz, who suggested approaching Rollins, the disconnected nature of how Tattoo You was brought to completion meant Watts and Rollins never shared any studio time.

“Probably just as well,” Watts said of missing out on recording with Rollins. “My goodness, I’d sit there and think, ‘Bloody hell, what am I going to do here?’ I’d feel like an impostor, because that’s the highest company you can keep.”

Side one continues with “Little T & A,” Richards’s customary turn on lead vocal duties, and the full-on roadhouse blues of “Black Limousine.” The sixth and final cut on the side is “Neighbours,” and nothing on the album exposes the ramshackle creative approach quite like it. The song sounds like the Rolling Stones trying all their shopworn tricks in the futile hope that an original tune will emerge. It’s three and a half minutes and feels like it goes on at least twice as long.

The flip side of the record delivers a string of ballads, most of which are undistinguished. Sure, “Worried About You” has a little soul tingle, and “Heaven” is strangely hollowed out, like a halfhearted attempt at Brian Eno–style atmospherics. But the flatfooted “Tops” and “No Use in Crying” are more indicative of how the string of more somber material feels. Tattoo You closes with the simple and affecting “Waiting on a Friend,” which kinda-sorta counters Jagger’s usual horny, chauvinistic lyrics by pining for a romantic relationship that goes deeper than surface attraction (“Making love and breaking hearts/ It is a game for youth/ But I’m not waiting on a lady/ I’m just waiting on a friend”).

Tattoo You was another strong seller for the Rolling Stones. In the U.S., it became their eighth straight chart-topping studio album on its way to quadruple platinum status, second to only Some Girls in their discography as far as total units moved. The concert tour that prompted the album was also a huge success, setting sales and attendance records across the country. Later, at the Grammy Awards, Tattoo You became the first Rolling Stones release to claim a trophy, winning for Best Album Package over the likes of Rick Springfield’s Working Class Dog and the Undertones’ Positive Touch. Of course, that award was given to art director Peter Corriston. The Rolling Stones themselves competed in the category Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal, where the entirety of Tattoo You was nominated. They lost to the Police and their track “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” one of about a jillion (okay, seventeen) gold-plated gramophones that Sting has wrapped his nimble fingers around.

Bank accounts might have been nicely padded all around, but it turns out that packed stadiums do not heal all wounds. Jagger and Richards remained at loggerheads. In the years that followed, new Rolling Stones studio albums were released less frequently and always accompanied by press coverage that suggested the end was nigh. There were fallow periods and wider and wider gaps between albums, and yet they never disbanded. Shockingly, the Rolling Stones endured.

To learn more about this gigantic endeavor, head over to the introduction. Other entries can be found at the CMJ Top 1000 tag. Most of the images in these posts come straight from the invaluable Discogs.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.