I read a lot of comic books as a kid. This series of posts is about the comics I read, and, occasionally, the comics that I should have read.

It was Dave Gibbons’s idea that Alan Moore should write a Superman story. The two had worked together a bit when their main source of income was producing comic book stories for various periodicals in their U.K. homeland. In the middle of the nineteen-eighties, Gibbons and Moore were establishing themselves in the U.S. through their efforts for DC Comics, Gibbons mainly as the artist for Green Lantern and Moore with groundbreaking writing on Swamp Thing. After a couple abortive attempts to find a suitable project for the both of them at their stateside professional home, Gibbons secured the assignment to provide the art for a limited series Moore was writing about the old Charlton Comics heroes that DC had recently acquired. At about the same time, Julius Schwartz, the legendary editor of DC Comics, asked Gibbons if he would draw that year’s Superman Annual. Gibbons agreed and asked who was writing it. Schwartz said no one was selected yet, and he responded by querying Gibbons about who he would like to be his creative companion on the issue. Gibbons immediately named Moore.

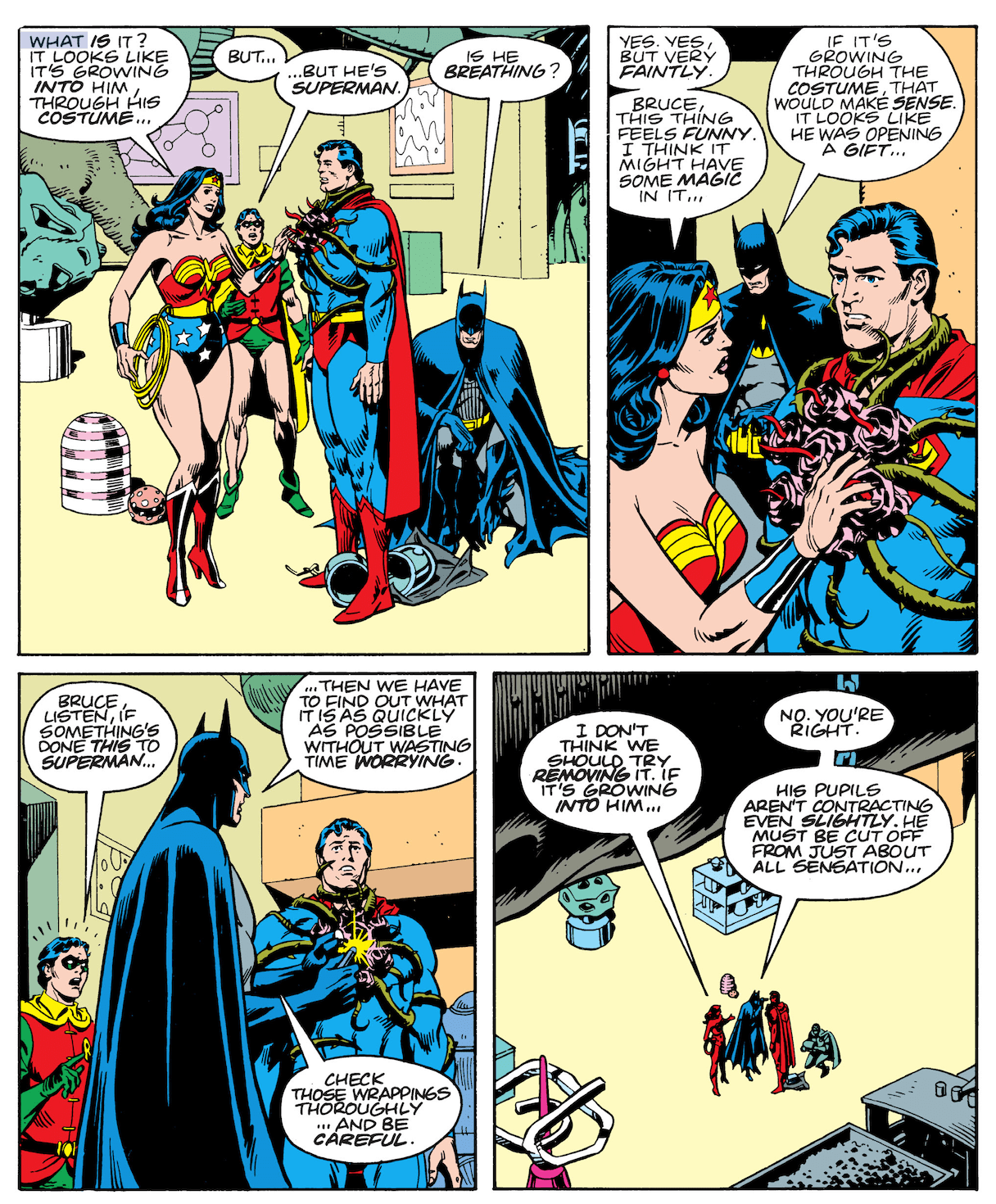

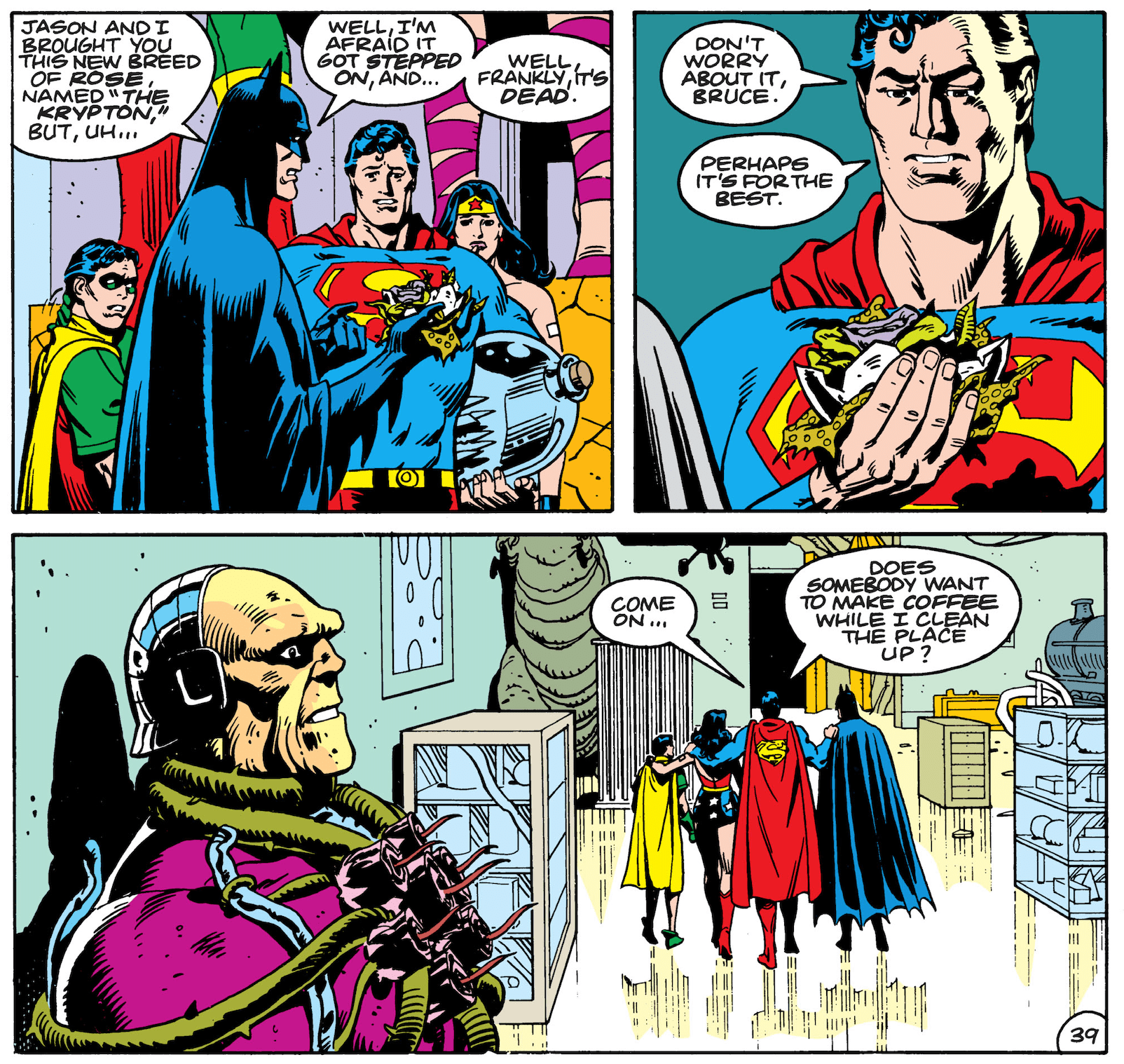

Superman Annual #11, published in the summer of 1985, featured a story by Moore and Gibbons titled “For the Man Who Has Everything…” It begins with Wonder Woman, Batman, and Robin visiting the Fortress of Solitude on Superman’s birthday. They come bearing gifts, only to discover that someone else’s present arrived first and really put a damper on Supes’s big day.

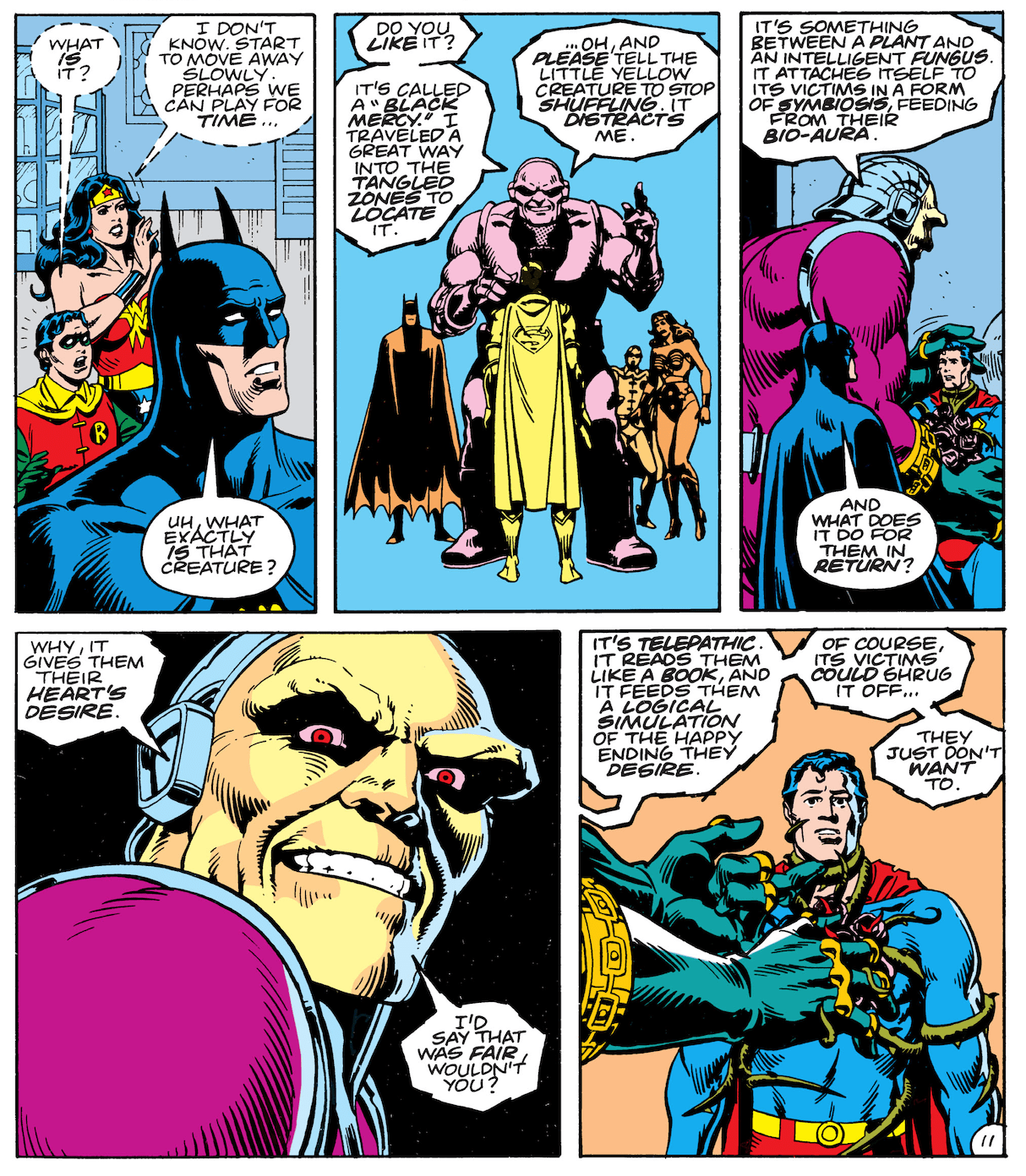

As Superman’s try to suss out what’s going on with the fauna affixed to their buddy’s torso, Moore provides glimpses of our main hero’s perception. He’s an adult on Krypton, living a workaday life with a wife and child. He also regularly visits with his disgruntled father, Jor-El, whose warnings of the planet’s imminent destruction decades earlier proved to be faulty. Jor-El now nurtures his grievances, taking disturbing comfort in the anger he carries for perceived slights against him.

Back in the Fortress of Solitude, Superman’s visitors encounter Mongul, the hulking foe who foisted the fearsome flower on him. Mongul explains that the alien growth in question is a Black Mercy, which has plunged Superman into a delusion he’s unlikely to escape from.

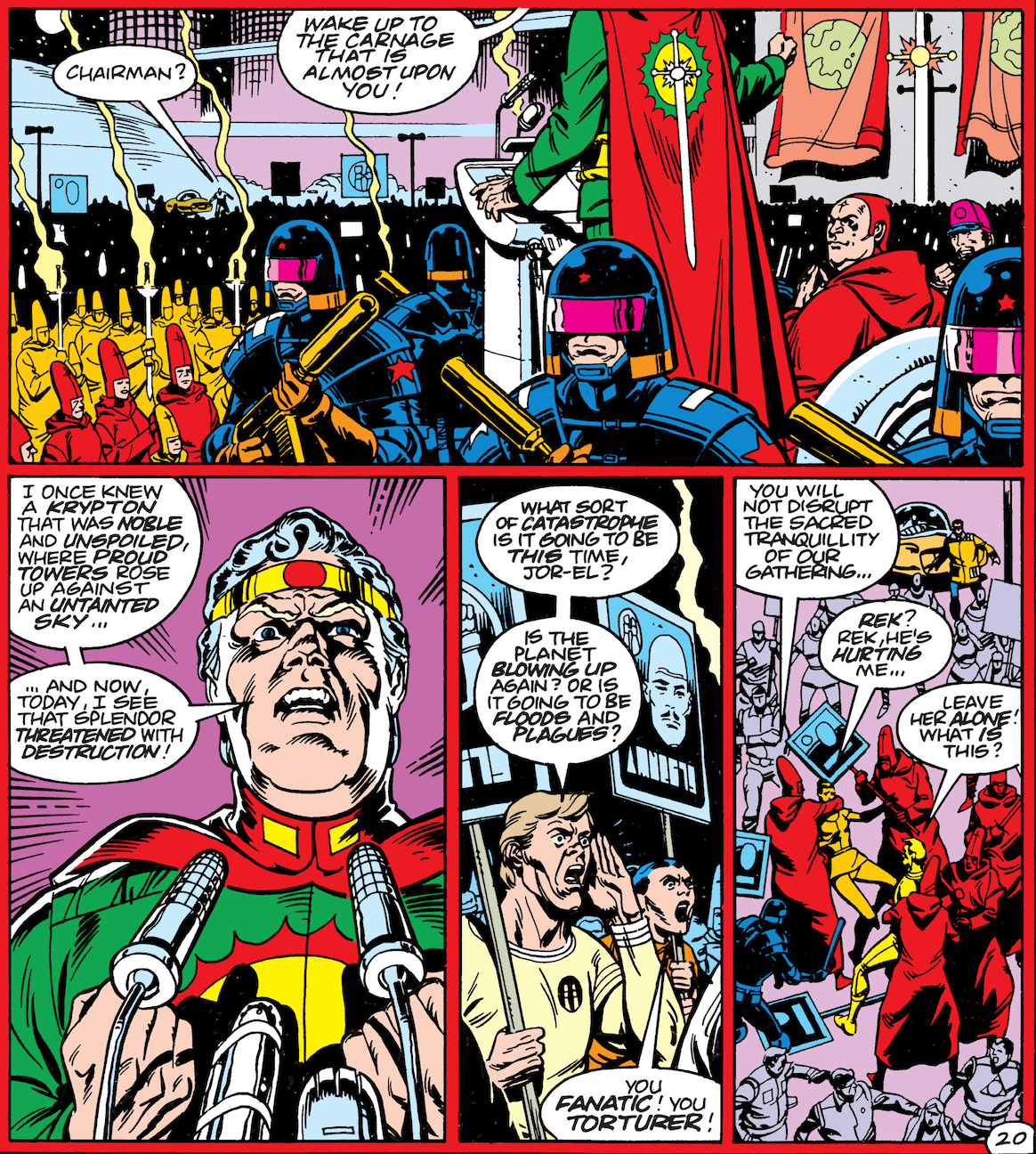

As Wonder Woman, Batman, and Robin do battle with Mongul, Superman’s vision of his homeworld grows more disturbing. Jor-El takes his bitterness and anger to the logical endpoint reached by all small men with access to the levers of power. He spits out false rhetoric of past greatness in their land and insists to his cultish disciples that he’s the only one who can restore that glory. When dissenting voices are raised, he dispatches anonymous militarized goons to terrorize them into submission.

Moore brings a compelling intellectual heft to this material. Without abandoning the fundamentals of big, booming superhero storytelling — the colorful dialogue, the dynamic fisticuffs, the devoted mining of past continuity, even the tinge of loving corniness — Moore traffics in big ideas of how society works and doesn’t work. It turns out that burgeoning fascism on Krypton looks a lot like burgeoning fascism anywhere else.

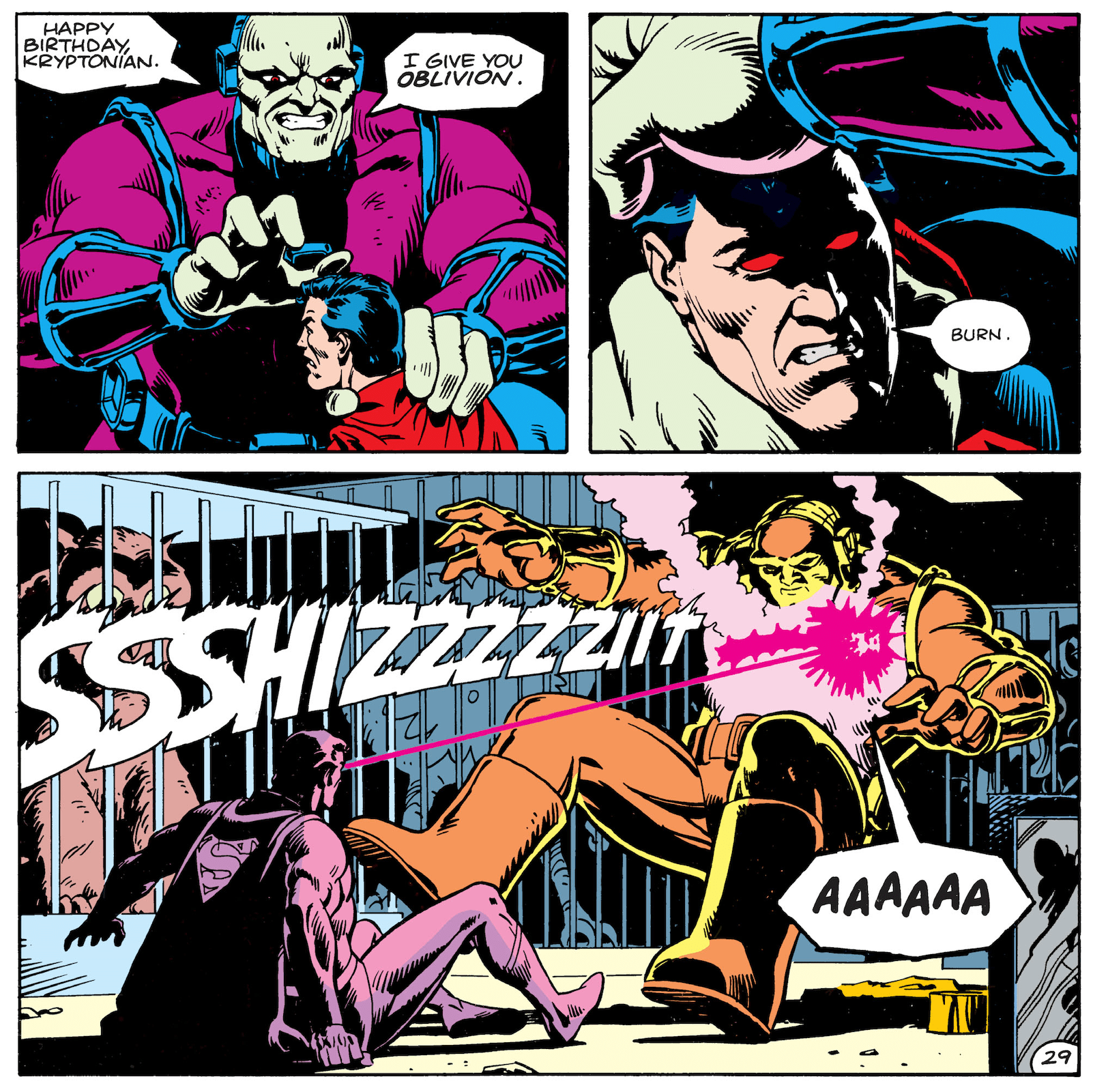

When Superman frees himself from the insidious mind control of the Black Mercy, he’s pretty peeved. In addition to the thoughtfulness he brings to his themes and political arguments, Moore is also good as just writing bad-ass scenes of powerful people using their metaphysical strengths.

Because of the epochal series by Moore and Gibbons that first hit comic shops almost exactly one year later, the entirety of the writer’s output for DC Comics is commonly seen as firmly deconstructionist. The earned and everlasting animosity Moore has for the publisher now compounds that view. I think that’s a misreading of how Moore approached a story like this. There’s a genuine reverence for the characters, including proper consideration for how this story must slot in with those around it. There have been many characters who wore Robin’s mask over the years. This issue was released early in Jason Todd’s tenure as the Boy Wonder, and Moore writes to that moment, emphasizing the mix of awe and uncertainty Jason would feel in his first real encounter with the greater scale of power and danger he would encounter when operating in Superman’s world. That seems like a small, basic thing, but current comic book writers don’t often care about thinking overall continuity when telling whatever story they want to tell. Moore approached his assignment with respect.

“I’ve worked on Superman, just using that character,” Moore said later. “If you’re a conscientious writer, you can’t help but feel the weight of myth and history that is connected…. It’s like if you were writing Sherlock Holmes. Sherlock Holmes is a massive figure in people’s minds. More massive than a lot of real historical characters — these figures have real weight. They might be just made out of words and paper, but their effect in the world can be massive, if they’ve got the right kind of mass, the right kind of gravity and momentum.”

Previous entries in this series (and there are a LOT of them) can be found by clicking on the “My Misspent Youth” tag.

Discover more from Coffee for Two

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.